HOSPITAL DESIGN FOR NURSE ATTRACTION

AND RETENTION—THE SECOND OF A THREE-PART SERIES.

THIS IS A RESEARCH COLLABORATION

BETWEEN HASSELL AND THE UNIVERSITY OF

MELBOURNE HEALTH SYSTEMS & WORKFORCE

UNIT DR. LUCIO NACCARELLA, PROF. JIM BUCHAN

MICHAELA SHEAHAN, MEGAN READING,

DR. AGUSTIN CHEVEZ, AND BRETT POLLARD.

Click here to read the original full report.

NURSES JUST WANT TO GET WORK DONE

The three elements of workplace design that most significantly affected nurses were space, proximity and indoor environment quality.

When you’ve got a job to do, you need the space, time and environment to get it done. Getting these elements right can directly affect nurses’ efficiency, the quality of care they provide, and staff morale. And these, in turn, can indirectly affect staff attraction and retention.

Image above: WA Comprehensive Cancer Centre,

Perth, Australia. Photography by Douglas Mark Black.

The study found that the three elements of workplace design that most significantly affected the nurses in their daily tasks were:

Spaces for:

- Storage

- Education and training

- Staff amenities for rest, meals and learning

- Patient and family areas

Proximity

- Walking distances

- Storage close to patient rooms

- Lines of sight

- Related hospital units or wards

Indoor environment quality

- Access to natural light

- Variable temperature

- Noise

- Odour

- Maintenance

These findings support existing research on the topic. Issues relating to space, and indoor environment quality are not new, or surprising, and none can be resolved in generalities—each ward design is unique to its location, infrastructure, models of care and other variables.

They are fundamental issues that designers address in every design project. However, the regularity with which deficiencies appear in nursing research indicates that there is still much work to be done to improve the daily working experience of nurses.

This work begins with the need to take a more user-centric view of the design briefing process by including nurses at the beginning of hospital design projects, and challenging assumptions and existing practices to suit evolving models of care.

Space

Space must evolve to support new technologies and models of care

In the tight budgetary and physical constraints of hospital management, space is precious. Regulations and standards provide guidance on how much space each area, each function, and each person may need.

But as models of care and technology now change much faster than published guidelines, the provision of space for various functions becomes conflicted and potentially compromised.

The design challenge is to provide more space—either by capturing space efficiencies elsewhere, and/or to make process changes to support working in less spacefor example, robotic medication delivery to allow less storage on the wards.

Education and training

“THERE’S NOT A DESIGNATED TEACHING AREA OR SEMINAR ROOM,

SO AT THE MOMENT WE USE OUR STAFF ROOM... IT’S SUPPOSED TO

ACCOMMODATE 14 PEOPLE PLUS AN EDUCATOR PLUS EQUIPMENT,

AND IT JUST DOESN’T WORK.”

Nurses are expected to pursue professional development and update their skills regularly. While some of this can be provided externally, hospitals also have their own internal programs.

Spaces dedicated to seminars, meetings, and access to online education platforms are increasingly important in the hospital workplace, but allowing adequate space for these activities is difficult.

Patient and family areas

“SPACE FOR PATIENTS, BETWEEN PATIENTS. APPROPRIATE SPACE

WHERE YOU CAN HAVE DIFFICULT CONVERSATIONS WITH PATIENTS

AND RELATIVES IN CONFIDENCE.”

When a patient arrives in a ward, often they bring with them an ongoing stream of family and friends, as well as a team of health professionals that require bedside access with the accompanying requirements for treatment, privacy and socialisation.

In addition to the bedside space requirements, a number of focus group participants lamented the lack of space for families. In the absence of adequate waiting areas for congregating visitors, the corridors and nurses’ stations fill with people, which can impede efficient work.

Adequate and appropriate storage

Appropriate storage is a key element of successful workplaces, and in the healthcare environment particularly. Convenient access to medication, and supplies, as well as larger equipment, were the most commonly cited issues in the focus groups.

The appropriation of spaces in hospitals for uses other than the original intention is common: treatment areas become offices, corridors become waiting areas, bathrooms become store rooms.

Many of the items requiring storage are bulky healthcare aids that are awkward to store, yet need to be readily accessed. Inadequate storage often results in ward bathrooms becoming improvised storage spaces.

“I’VE NOTICED OVER TIME THAT A LOT OF THE

AREAS THAT WERE USED FOR PATIENTS HAVE

BECOME STORAGE AREAS.”

“OUR EQUIPMENT IS IN A BATHROOM, SO IF A

PATIENT WANTS TO USE A BATHROOM, YOU

PULL OUT ABOUT THREE COMMODES, A

WHEELCHAIR AND A BIG MONASH CHAIR....

IT’S RIDICULOUS.”

A move to centralised storage of equipment with a team that maintains, cleans and distributes equipment as it is needed has been implemented successfully in many new hospitals, including the Gold Coast University Hospital in Australia. This type of system allows more efficient hospital-wide use of equipment, less duplication, and more patient time for nurses.

Nurses spend a considerable amount of time as hunters and gatherers—walking from patient rooms to the nurses’ station and other areas.4 This was reflected in a number of comments in the focus groups about quick access to medications and other consumables.

“A LOT OF THE WARDS I HAVE BEEN ON (HAVE HAD) LOVELY

BIG WINDOWS AND LOVELY SPACE, BUT THEN HOW MUCH IS

TOO MUCH SPACE? ...YOU’VE GOT HEAPS OF STORAGE AT

THE FRONT BUT THAT MEANS YOU’VE GOT TO WALK THREE

KILOMETRES TO GET DOWN TO YOUR PATIENTS. IT’S ABOUT

FINDING THAT BALANCE ISN’T IT?

“STORAGE AT OR NEAR THE BEDSIDE, OR CLOSE TO THE

FOUR BED ROOMS WOULD SAVE ON HAVING TO HAVE

THESE BIG STORAGE ROOMS, AND NURSES’ TIME GOING

TO GET THINGS THEN COMING BACK TO THE PATIENT.”

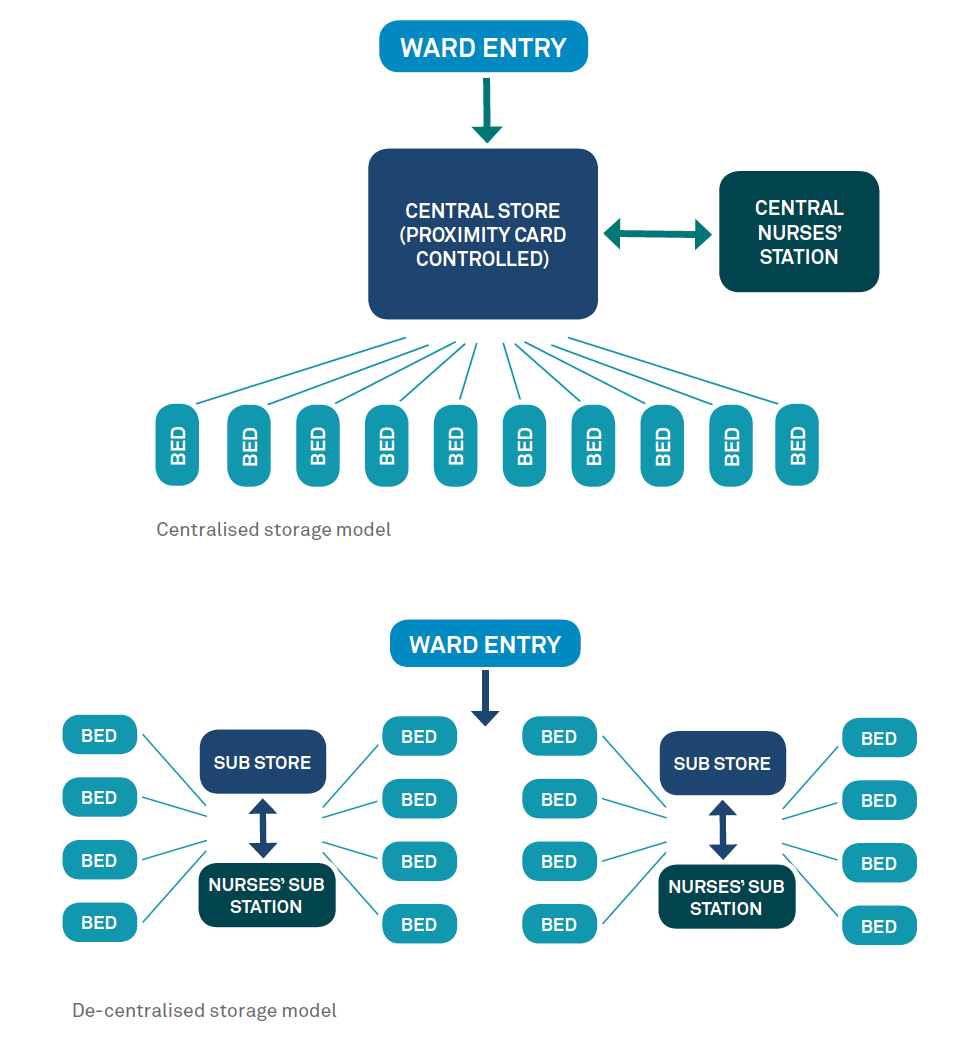

Adequate and appropriate storage

In addition to the trends in storage for large equipment, the storage of small consumables in hospitals is changing. With the advent of “just in time” supply and delivery of stock, there is a move to provide bulk storage space for trolleys pre-packed with the day’s requirement of consumables.

Bulk storage is usually located centrally and is controlled by swipe card. While enhancing security of medications, this requires staff to walk to this central location many times in a day.

Bulk storage is usually located centrally and is controlled by swipe card. While enhancing security of medications, this requires staff to walk to this central location many times in a day.

Automated medication stations with finger print access are also a new development intended to overcome issues of medication security.

At the New Karolinska Hospital in Stockholm, large storage areas will not be required in wards as equipment, consumable and medications will be ordered digitally, and delivered either by pneumatic tube or by remote controlled robots.11

This type of trade-off between security of medications and proximity is not uncommon in hospital planning.

These examples serve to remind hospital planners and designers that models of care and management can have significant ramifications for nursing staff, and their methods of working, and should be carefully considered in the early phases of design.

Staff amenities

One of the key themes emerging from the focus groups was that poor hospital design can contribute to a culture that de-values what nurses do and how they work. This affects job satisfaction, and in turn, staff attraction and retention.

The psychological contract—an unspoken understanding of mutual obligations between employers and employees12 is under threat in hospitals. Nurses perceive a lack of respect for their work as hospitals pursue business models focussed on cost control and patient throughput.

Our research suggests that one of the expectations of nurses in their psychological contract is the provision of a safe, comfortable and effective workspace, for the benefit of both the patients and staff.

Time out for nurses

Nurses repeatedly noted the lack of space away from the immediate demands of patients for paperwork, learning and meal breaks. High rates of staff turnover in the nursing profession are linked to stress and burnout, and consequently staff morale, productivity, medical error and patient satisfaction.10,13

ONE OF THE KEY THEMES EMERGING FROM THE

FOCUS GROUPS WAS THAT POOR HOSPITAL DESIGN

CAN CONTRIBUTE TO A CULTURE THAT DE-VALUES

WHAT NURSES DO AND HOW THEY WORK.

The provision of comfortable areas for meal breaks (close to, but separate from, the clinical area) are an important inclusion to combat the intense nature of work that nurses confront daily. Yet some hospitals do not provide the most basic break facilities.

Adequate space for documentation tasks, handover meetings, or online training is also a visible demonstration that the hospital respects and values the important work that the nurses do.

Lessons from other sectors

HASSELL has introduced spaces into new healthcare environments based on our learning from the education, research and commercial office sectors, where employees are increasingly benefitting from centralised spaces that blend social, work and learning functions.

At the Rockhampton Hospital in Australia, administrators recognised the importance of providing a large and inviting staff space to attract and retain highly skilled staff to a regional facility. At the Critical Treatment Hospital in Hampshire, UK, the Central Staff Zone is based on the concept of an airport lounge with changing areas and toilets provided, as well as flexible seating, working and education space.

These types of spaces provide much needed respite from the daily stresses of healthcare, but also encourage staff interaction and demonstrate to staff the value the hospital places on their contribution.

Proximity

Proximity for nurses means a variety of things—safety, efficiency, comfort, reliability. The nurses in our focus groups repeatedly raised the need for proximity, both physical and visual, to optimise lines of sight to patients and staff and walking distances to storage, nurses stations and related units.

Fast access to equipment and staff in an emergency can be crucial. Visual connection for surveillance of patients can help to reduce falls, and consumables stored close to where they are needed saves tired legs at the end of a shift. But growing space requirements for technology, equipment and patients regularly challenge designers to maintain a workable balance.

Lines of sight to patients

While there is still debate about the cultural, social and spatial benefits of multi-bed patient rooms, the number of single bed rooms in new hospitals is increasing on the basis of evidence of shorter patient stays, reduced infection rates and medical errors, and improved privacy.3

The single bed room has helped to deliver patient-centred care, but has come at a price: nurses walking further to attend to patients, and restricted sightlines.14 Nurses understand and largely support single bed rooms, but worry about the safety of patients when lines of sight are interrupted.

The single bed room has helped to deliver patient-centred care, but has come at a price: nurses walking further to attend to patients, and restricted sightlines.14 Nurses understand and largely support single bed rooms, but worry about the safety of patients when lines of sight are interrupted.

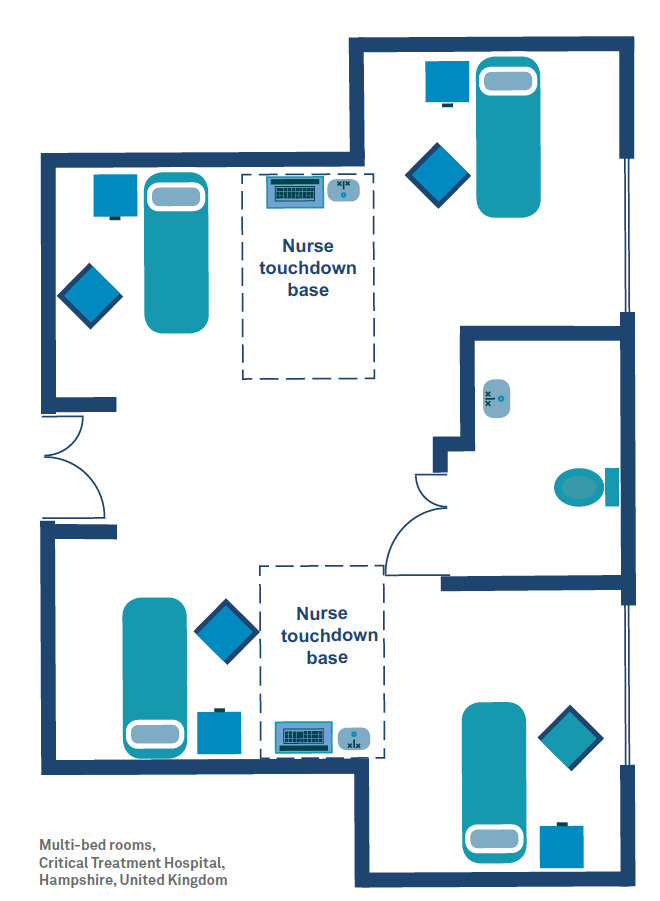

In response to these concerns, the Hampshire Critical Treatment Hospital will have multi-bed rooms that maximise visibility and maintain privacy levels (see left diagram).

The beds are located in niches that provide a visual barrier between patients without compromising general surveillance. “Touchdown bases” with the necessary equipment and technology are located strategically between the beds to enable direct sightlines between patients and nurses.

Technology

Technology increasingly has a role to play in improving connections with patients and staff, with the use of mobile devices to track the nearest staff and equipment, as well as patient records and identification.

Nurses at the Texas Children’s Hospital use a smartphone to text, talk, access resources, receive alarm queues, and determine staff availability.15 Electronic whiteboards in patient rooms are also becoming common for communication between staff, patient and families.

Walking distances

Studies have shown that nurses can spend up to a third of their time walking around the ward.4 This can cause fatigue, and detracts from time spent with patients. Proximity to beds, administration, storage and other related units can all make a difference to a nurse’s work day.

Nurses’ stations

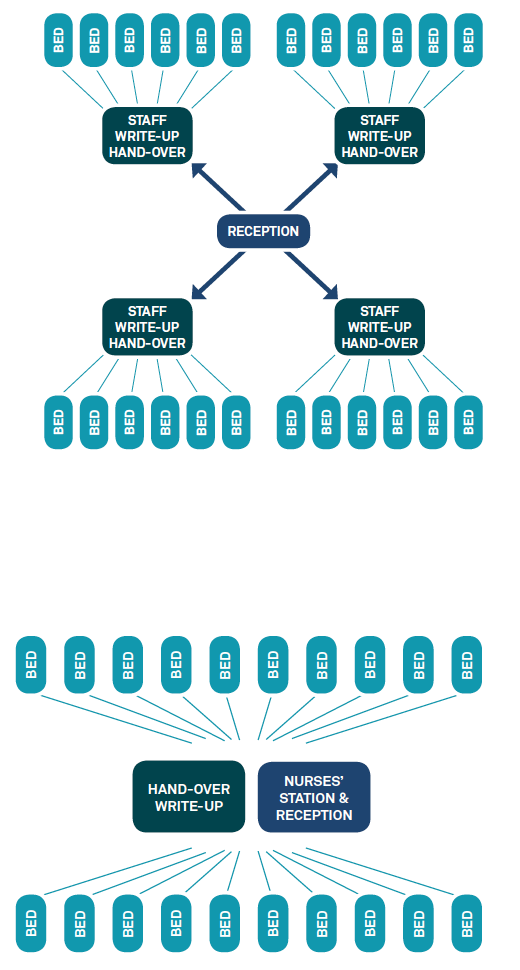

Major decisions relating to how care is coordinated will influence design outcomes. This is particularly true of the epicentre of nurse work—the nurses’ station, a space that was raised often in the focus groups, particularly in relation to proximities.

There are two approaches that can be adopted: a de-centralised model and a centralised model (see diagrams below).

Neither model solves all the issues, and both can be seen to have significant benefits. The alignment of the model with the prevailing organisational culture within a hospital (or even an individual ward) must be considered during the early phases of design to ensure that the most appropriate setting for both the staff and the patients is provided.

De-centralised nurses’ station

De-centralised nurses’ station

The nurse station is often not occupied as nurses are delivering their care. A full-time administrative Ward Clerk is required at reception to ensure patients’ families are able to locate staff.

Advantages

- Shorter walking distances

- Quieter and more discreet

- Less physical barriers between staff and patients

- Clusters of patients provide nurses with more autonomy

Disadvantages

- Junior staff may not have access to role models or fast assistance

- Staff can spend more time searching for colleagues

- No central point of contact if ward clerks are not employed after hours

Centralised nurses’ station

The centralised nurses’ station provides a focal point for all care activities, and storage for the key clinical records.

Advantages

- Supports collegiate information sharing

- Obvious staff point for visitors

- Easier managerial oversight of staff

Disadvantages

- Sightlines to bedrooms more difficult to achieve

- Patients can feel left alone if staff congregate at central point

- Staff must walk back to central location to access information

- Busy and potentially noisy

- Nurses may feel less autonomyous

- Promotes a process-orientated approach that may not match staff values

Indoor environment quality

Nobody really wants to visit a hospital. It usually means someone is sick, but also recalls our collective memories of older hospitals—long corridors smelling of disinfectant, the murmur of discomfort, and a lack of windows.

For hospital staff, the aesthetics and maintenance of the workplace serve as a daily reminder of the value their employers place on their work.

Nurses identified a number of environmental qualities that affect their daily work experience, including temperature, noise, odour and colour, but the main factors were:

- Access to natural light

- Maintenance

“… IT JUST LOOKED REALLY MESSY… DISORGANISED

AND CHAOTIC AND ALMOST AS IF NOBODY CARED.”

Natural light

“YOU COULDN’T SEE ANY NATURAL LIGHT AT ALL.

IT JUST FELT REALLY OPPRESSIVE TO ME.”

“I LIKE HOW YOU CAN WALK ALONG DIFFERENT CORRIDORS

AND ALMOST AT ANY POINT YOU CAN ACTUALLY SEE OUTSIDE,

AND THERE’S NATURAL LIGHT.”

Hospitals are challenging environments to build and maintain, but access to natural light is a crucial element in a well designed facility. Green field and new build hospitals present opportunities to provide this type of design element, albeit within budgetary constraints.

The refurbishment, rebuilding and extension of older hospitals presents very real challenges, particularly in achieving natural light penetration within often labyrinthine existing spaces.

Narrow floor plates, courtyards and atriums are common design elements that seek to provide staff and patients with much needed access to natural light.

Maintenance

It is hardly surprising to learn that nurses want their workplace to look neat, clean and attractive—most people do. A recent post-occupancy study of a new Australian hospital16 found that the cleanliness and ease of maintenance was important to staff. In particular a large and open atrium space at the entry point provided a welcoming start to the working day.

“I DON’T LIKE SEEING THINGS THAT ARE BROKEN,

WHERE THERE’S A BIT OF ROPE HANGING DOWN

FROM THE VENT, THERE’S MOULD AND WATER

MARKS OVER THERE. IF WE LOOK LIKE WE CARE

ABOUT OUR PEOPLE WE NEED TO LOOK LIKE WE

CARE ABOUT OUR HOUSE.”

The degenerating condition of one of the hospitals in the study was a significant source of concern for nurses—particularly for patient safety, but also as a measure of how much hospital management valued staff. Comparisons to another (newly built) site were numerous and pointed, and indicated that the level of maintenance of a facility reflected the standard of care those within its walls would receive.

References

- PriceWaterhouse Coopers (2004). The role of hospital design in the recruitment, retention and performance of NHS nurses in England. Website at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110118095356/http:/www.cabe.... n.pdf

- Centre for Workforce Intelligence (2014) Horizon 2035 International responses to big picture challenges. Website at www.cfwi.org.uk/publications/horizon-2035-international-responses-tobig-...@@publication-detail

- Ulrich, R., Zimring, C., Zhu, X., DuBose, J., Seo, H. B., Choi, Y. S., et al. (2008). A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. Health Environments Research and Design Journal, 1(3), 61–125

- Joseph, A. (2006) The role of the physical and social environment in promoting health, safety, and effectiveness in the healthcare workplace. Issue Paper #3, Centre for Health Design. Website at www.brikbase.org/content/role-physical-and-social-environment-promoting-...

- Rechel, B; Buchan, J; McKee M. (2009). Capital investment and the health care workforce. Chapter 5 (pp 85). In Investing in Hospitals of the Future. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Website at www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/98406/E92354.pdf

- Health Workforce Australia (2014)Health WOrforce Australia - Nurses Report. Department of Health Website at www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/34AA7E6FDB8C16AAC...$File/AFHW%20-%20Nurses%20overview%20report.pdf

- Jones and Gates (2007). The Costs and Benefits of Nurse Turnover. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing

- Ecoff and Brown (2010) Evidence Based Architectural and Space Design Supports Magnet: Empirical Outcomes JONA:40(12):505-508

- Anderson, G. (2013) Design’s Role in Attracting and Retaining Healthcare Workers, Healthcare Design Magazine Website at www.healthcaredesignmagazine.com/article/design-s-roleattracting-and-ret...

- Chan, C.CCA; McBey, K; Basset, M; et al (2004). Nursing crisis: retention strategies for hospital administrators. Research and Practice in Human Resource Management, 12(2): 31-56

- Nya Karolinksa Solna, (2013). On the way to the new heatlhcare of the future. Website at http://www.nyakarolinskasolna.se/globalassets/dokument/nks_broschyr_eng_...

- Hall, R. (200x) Psychological Contracts: An Introduction to the Concept. Website at www.lrrpublic.cli.det.nsw.edu.au/lrrSecure/Sites/Web/13289/ezine/year_20...

- Dawson, Stasa, Roche, Homer and Duffield (2014) Nursing Churn and Turnover in Australian Hospitals”. Nurses perceptions and suggestions for supportive strategies. BMC Nursing Website at http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6955/13/11

- Maben, J. (2009) Spendid Isolation? The pros and cons of single rooms for the NHS. Nursing Management. 16, 2, 18-19. Website at http://dx.doi.org/10.7748/nm2009.05.16.2.18.c7010

- Trossman (2015) Texas hospital approaches technology with an eye to patient safety and nursing practice. Website at www.theamericannurse.org/index.php/2013/11/04/texas-hospitalapproaches-t...

- HASSELL (2015) Internal document

- Granath, J; Lindahl, G &d Rehal.S. (1996). From Empowerment to Enablement. An Evolution of New Dimensions in Participatory Design. Logistik und Arbeit. Website at www.design4change.com/LinkedDocuments/From%20Empowerment%20to%20Enableme...

- Coughlin, Fulton Suri and Canales, 2007. Prototypes as (Design) Tools for Behavioral and Organzational Change .The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, Vol. 43 No. 1, March 2007 1-13. Website at https://www.ideo.com/images/uploads/news/pdfs/Prototypes_as_Design_Tools...