I walk by William Rawn’s Cambridge Public Library extension twice a day on my way to and from work. I love the transparency of the south façade. It is sharp and crisp, and I can see right through to all of the exploring, socializing, reading, and working taking place within. When I go into the library for research or study, however, I tend to move quickly away from the openness of the new building into the old one. I find a semi-enclosed quiet spot away from the crowds, turn off social media, and get to work.

In the world of educational facilities, the buzzword over the last 10 years has been “collaboration,” with the focus on shaping physical space to support students’ cooperative efforts. Great energy has been put into designing classroom furniture to enhance students’ ability to work together. Classrooms have been designed to allow students to easily share ideas, efforts, and experiences. Even the rise of the now ubiquitous academic “learning commons,” in place of the traditional library, came in part from the impetus to create more group or social learning spaces.

In the world of educational facilities, the buzzword over the last 10 years has been “collaboration,” with the focus on shaping physical space to support students’ cooperative efforts. Great energy has been put into designing classroom furniture to enhance students’ ability to work together. Classrooms have been designed to allow students to easily share ideas, efforts, and experiences. Even the rise of the now ubiquitous academic “learning commons,” in place of the traditional library, came in part from the impetus to create more group or social learning spaces.

The seemingly indisputable logic behind all of this comes largely from the business world. As Malcolm Gladwell has written on his blog, “Innovation — the heart of the knowledge economy — is fundamentally social.” Business tells us that innovation requires collaboration; therefore, we should be training our students to work in groups. As humans, this reasoning insists, we do better work when we know how to work together effectively in teams.

But what if Gladwell and the rest are wrong? In her bestseller Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, Susan Cain disputes the power of collaboration theory. As part of a longer argument defending her thesis, she describes innovators such as Steve Wozniak toiling alone in his cubicle night after night in his pursuit to create the first personal computer. She provides a letter from the solitude loving Charles Darwin replying to a social invitation: “My Dear Mr. Babbage,” he writes, “I am very much obliged to you for sending me cards for your parties, but I am afraid of accepting them, for I should meet some people there to whom I have sworn by all saints in heaven, I never go out.”

Some research bolsters Cain’s thesis even within the business world. In “The Brainstorming Myth,” a Business Strategy Review article from 2000, organizational psycholo-gist Adrian Furnham indicates that performance gets worse as group size increases. He writes, “If you have talented and motivated people, they should be encouraged to work alone when creativity or efficiency is the highest priority.”

Given that there is at least uncertainty over the benefits of collaboration, perhaps it is time to rebalance our thinking on the types of spaces students need to learn, to think, and to be creative. Are there at least some of us who need privacy and solitude to do our best work?

The Roeper School in Birmingham, Michigan is exploring that theory. Our firm, HMFH Architects, has been hired to design a new dining hall and library for this k–12 school for gifted students. The initial design solution called for infilling the courtyard of its doughnut shaped building with a learning commons that included group study areas, social spaces, and food service. The proposed learning commons would open directly into the existing building through the renovation of the library. The initial concept included a range of spaces for different sized groups and types of activities, but the emphasis was on providing opportunities for collaboration.

The feedback was generally positive, but there were voices with a persistent question that we couldn’t ignore. The voices were from the students, and they were asking, “Where do I go to be alone?”

Cain would not have been surprised by the question. She reports on a series of studies done in the 1950s at the University of California/Berkeley on the nature of creativity. “One of the most interesting findings, echoed by later studies, was that the more creative people tended to be socially poised introverts and ‘not of an especially sociable or participative temperament.’” The students at Roeper, who tend to rank high in originality and curiosity, are likely to fall within that characterization. They were eager to have their renovated school support the way they operate and learn.

Cain would not have been surprised by the question. She reports on a series of studies done in the 1950s at the University of California/Berkeley on the nature of creativity. “One of the most interesting findings, echoed by later studies, was that the more creative people tended to be socially poised introverts and ‘not of an especially sociable or participative temperament.’” The students at Roeper, who tend to rank high in originality and curiosity, are likely to fall within that characterization. They were eager to have their renovated school support the way they operate and learn.

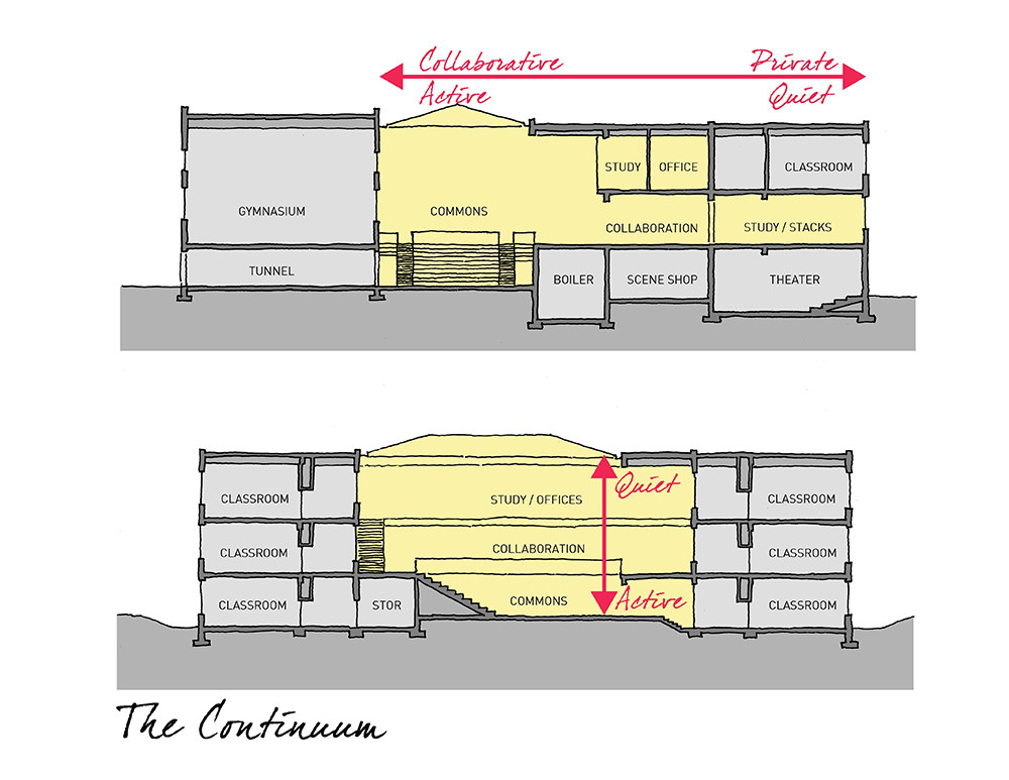

The revised approach for Roeper has become known as the “Continuum,” and for obvious reasons. The Continuum will provide a spectrum of spaces from large active spaces at one end of the building through a range of small group areas and ultimately to quiet individual study spaces at the other end. The design provides opportunities for more enclosed rooms than originally envisioned, but the Continuum also allows students to enter at the level of activity and social interaction that feels right simply by deciding on which entrance to pass through.

Roeper is not alone. The recently opened Brody Learning Commons at Johns Hopkins University, designed by Shepley Bulfinch, is a careful mix of solitary and group study. Although it does have an open commons space for more collaborative activities, that is complemented by 15 small group rooms and the very popular Quiet Reading Room, which, according to Shepley’s senior library planner, Kelly Brubaker, “is intended to promote an atmosphere for focused research and individual scholarship within the larger facility.”

We live in an era that elevates openness and connections. We want our lives to be full of experience and information. We want our workplaces to provide plentiful opportunities for meaningful interactions. We expect our institutions to be open and transparent. We shape our architecture to those goals whether in our open office plans, the transparent façades of our high-rises, or in schools with high levels of interconnectedness. But maybe those students at Roeper are on to something. Maybe in the midst of all that openness and interaction we also need to be creating something else as well. Perhaps we need to be carving out both time and place for solitude. ![]()

This article was originally written by Laura Fernwick for Architecture Boston and reposted in its entirety from www.architects.org. To view the original article, click here.