UP OR OUT? ADDRESSING THE DENSITY DILEMMA.

As urban populations swell, cities face a fundamental question: should they go up—or go out? Which is the best way to manage growth? And can you increase density without compromising social or environmental outcomes?

Global cities grappling with density—as well as challenges to connectivity, affordability, and amenity—often look to Hong Kong as an instructive model. So we decided to explore the potential for Hong Kong to become even denser.

By understanding the physical, social, and environmental dimensions that constrain the city’s future growth, we could speculate on new spatial models for urbanisation.

Three measures that all matter

There are three ways to measure and understand urban density—through floorspace, dwellings, and people per hectare—and each needs to be optimised within a dense city environment.

Density, in large part, can be delivered through the engineering of taller, thinner, more efficient building structures and through shared urban infrastructure, such as transportation, water, and energy networks.

But these engineering solutions are less effective when we consider the third measure of density—people. That’s because people relate more closely to the provision of social infrastructure, such as open spaces and parks, community facilities, and other public and private amenities.

Often, as we intensify the city, we reduce the area available for public space and public infrastructure—even though these become even more critical for communities living in dense cities. And without them, we do not deliver the "social license" for density: we make more buildings and more dwellings, but we do not necessarily provide the homes people want.

So we looked at whether we could create a truly vertical system of public spaces and public infrastructure. Could this system support the idea of a superdense city?

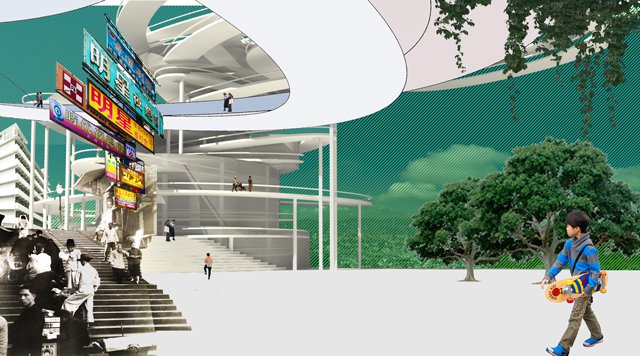

A vertical main street that meets everyone’s needs

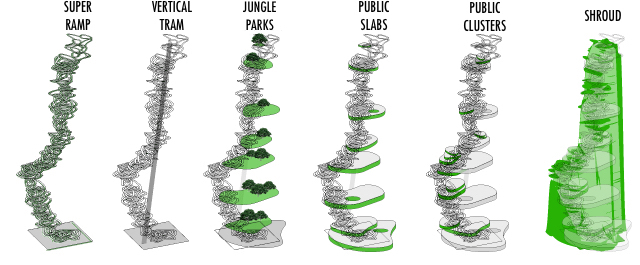

Our proposal begins with the creation of a continuous ramp. It’s the most public, most accessible, and most flexible circulation path we could imagine—more than 10-kilometres long and winding its way 500 metres into the sky.

We then augment this slow path with a faster option—a rapid transport mode that stops every 80–100 metres. At each stop, we propose new jungle parks—lush, generous, and open to the elements.

Below these are public slabs containing hospitals, libraries, schools, markets—the social infrastructure required for living and working populations. And there are also clusters of economic activity, retail, workplace, and enterprise centres—like a vertical version of street-facing shopfronts.

Around this whole system is a structural shroud, creating a sense of enclosure and protection, as well as the potential for landscape propagation.

We have now essentially created the idea of the vertical main street, with fast and slow movement, open spaces, and social, economic and ecological infrastructure.

New homes, new workplaces, new neighbourhoods

This system can be a catalyst for the renewal of the surrounding neighbourhood, unlocking the potential for thousands of new homes, new workplaces, and new neighbourhoods.

Upper-level connections between buildings create a three-dimensional movement network across this new neighbourhood. And much of life can be lived well above the ground plane. In fact, the more self-reliant this system becomes, the more effective it is.

In a city of verticality—from towering landscape forms to skyrise commercial buildings—these towers could create an evocative new image for cities that are constantly finding new ways to innovate and experiment within the urban environment.

This article was reprinted through the courtesy of HASSELL Studio. Read the original article here. Read the full report, "Superdensity: a New Model for Vertical Urbanism," here.