Former CEO and Global Executive Chairman of Woods Bagot Ross Donaldson oversaw the global growth of the practice from a relatively small Australian firm to now being the 7th largest in the world. An architect, urbanist, and academic, he treated the practice itself "as a design exercise with all its functional elements and communication patterns and complexities releasing the full entrepreneurial and creative energy of the constituent parts whilst continuing as a fully integrated holistic entity."

ABOUT STYLE

Steve Napier: Inevitably for a 147-year-old practice, Woods Bagot has embraced a wide variety of architectural styles. What would you say is the contemporary Woods Bagot signature?

Ross Donaldson: Style is not a relevant concept for the twenty-first century.

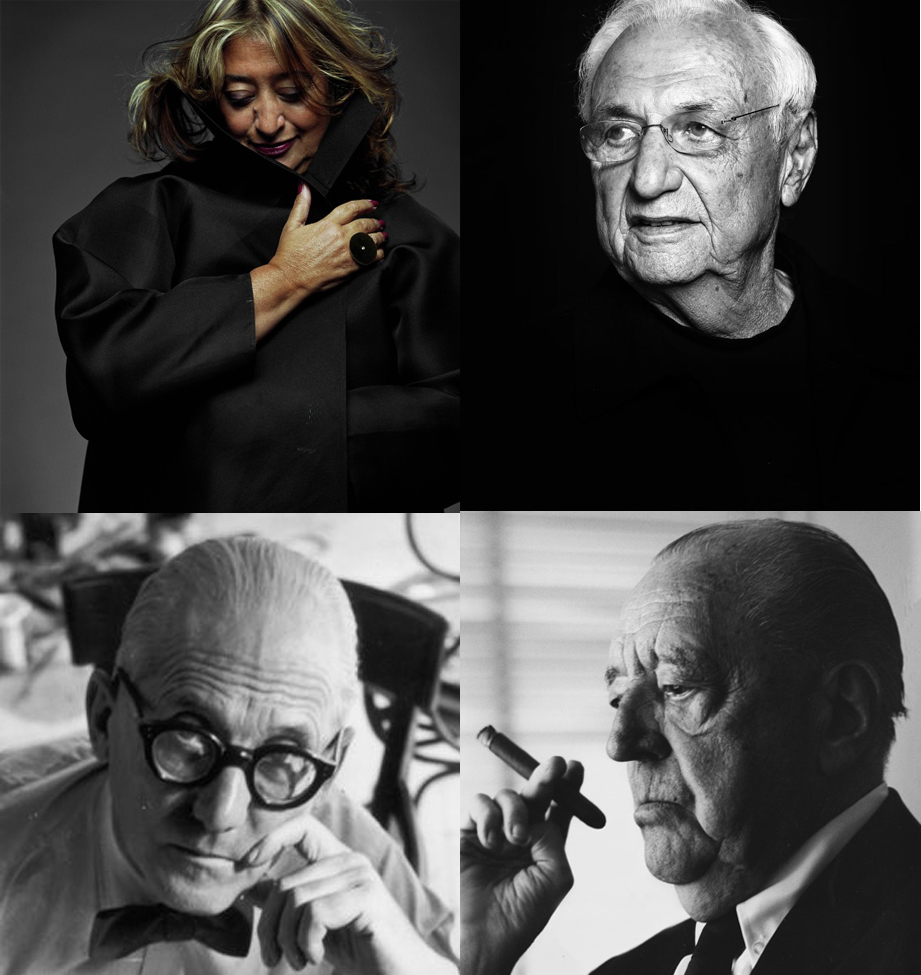

Whilst a great deal has been made of architects such as Zaha Hadid and Frank Gehry being the most prominent “stylists” of the late-twentieth century, they have had little or no discernible impact on the way architecture is done apart from fuelling the software-driven fascination for "shape" architecture, with the preoccupation with form that has little to do with programme. Certainly not in the way Le Corbusier or Ludwig Mies van der Rohe did in the earlier fluorescence of Modernism in the twentieth century. The output of the latter two, while it only comprised a modest portfolio of built work, fundamentally transformed the way buildings were done. Architects everywhere sought to emulate Le Corbusier and van der Rohe with their own variations of the pair’s design fundamentals, albeit hardly ever nearly as well. The vast majority of built work, therefore, was of a pretty poor design quality as a result—unsurprisingly, as the prevailing mode was one of imitation.

Today, things are different, and as a result, a lot more architectural work is of better quality.

For Woods Bagot, the project starts with a deep interrogation of its programme. The design fundamentals were defined by seeking an innovative and sometimes experimental optimisation of the performance requirements and associated behaviours of the buildings users, be they office worker, student and teachers, research scientists, or events delegates. This will drive the articulation of the interior concept and its internal forces exerting on envelope definition. The envelope will be formulated through the interface between these forces and the urban or landscape context. This is very different from the architecture of the likes of Gehry or Hadid, where the thinking is driven by the requirement of a stylistic regime wherein the built fabric is comprised of a set number of forms and materials, fabricated in a formulaic arrangement of forms.

Our architecture cannot be defined through a preset of materials or forms; it comes from the serious investigation of the project’s performance needs, which are almost invariable driven by some notion of efficiency and effectiveness of the performers within the building—again, be they learners, workers, researchers, delegates, and so on.

This is also why you cannot define the style of the other prominent practices of today—BIG, OMA, etc. In Australia, at a very different scale of work with great architects like Sean Godsell and John Wardell, it's also difficult to define a style, but you can talk about an “attitude” and certainly a marvellous talent that is brought to their project.

INTEGRATION

SN: How does this signature manage to permeate all the different studios even if they are located in different regions around the world, with each region having its own cultural and design sensibilities?

RD: The more Woods Bagot has become clear in its disciplined commitment to this form of design, the better the work has become. It is also the glue that binds the company together globally.

This framework can accommodate a broad spectrum of design sensibilities and releases all the talent. It is the antithesis of a single-identity practice, where every designer has to second-guess what the name architect in HQ will be thinking or await the direction of the identity leader. It is also why such practices are naturally self-limiting. You cannot scale while second-guessing one person’s likely design action.

And it certainly is not leveraging the full design talent of the whole practice. Thus, more clients will get a much higher quality of service, and the project will consistently be of a higher quality.

The full potential of the talent and specialist knowledge of the whole group is released to exercise its full initiative, doing so within the coherence of the integrated design-practice focus.

This is, in part, a factor that has also fuelled the dramatic growth.

THE PRACTICE AS A DESIGN EXERCISE

SN: Please give us a glimpse of how your treating "the practice—itself—as a design exercise” infused your decision making. How has this framework changed Woods Bagot organisationally?

RD: A business is comprised of a number of functional parts distributed in space/geography. Each of these has specific functional parts with discrete functionality contributing to the optimum operation of the mechanism/organism. A key element in this optimum operation is the circulation of communication between and amongst the functional parts.

There are clear operational outputs expected from the mechanism/organism and flows that should be clearly defined.

On one level, it’s simple and obvious—this describes both a business and a brief for an architectural project.

If you focus on the operational needs and effectiveness of each of the parts individually and initiate strategies to facilitate the smoothness of communication—economising on the perfunctory parts and investing in the critical high-performance elements—you will achieve optimum performance and financial performance.

This is why there is so much discussion of design in the management theory world and why many are crossing these previously entirely separate domains. There is a fundamental relationship between the organisational design of a company or business and its performance and culture.

MARKET SECTORS

SN: Because of its size, reputation, and history, Woods Bagot will always have the ability to land big-ticket projects. But is there a particular sector the practice was most excited about during your leadership of Woods Bagot?

RD: It’s less about particular sectors and more about the fact that the trend is towards blurring the boundaries of these. A key theme of recent years has been the notion of “agility”—agility of space to accommodate a wide variety of behavioural modes. The previous practice of linking a specific spatial type with a specifically defined function or action is disappearing very quickly, particularly amongst innovative organisations, be they universities, tech corporations, event spaces, or airports. We are seeing a mass movement in co-working business models: Airbnb is rattling the foundations of the hospitality industry; as learning becomes more of a social and experiential process, we are seeing the end of the lecture theatre in schools and universities; and airports are competing with each other to command the reputation for the quality of its users’ experience.

Innovation is driving performance in these leading organisations and institutions. In this age of “disruption,” it has become a truism that (as Gary Hamel first put it) successful corporations of the 21st century will be able to “change as fast as change itself.” This agility at the organisational level requires the architect to also deliver it at the interior spatial level.

It’s a very exciting time, as it drives continual innovation of our practice of architecture—the successful architectural practices of the 21st century will exhibit this capacity for change, including how they are themselves structured organisationally.

SUPERSPACE

Executive Chairman of Woods Bagot

SN: Please explain the concepts of SuperSpace and SuperTypologies that were adopted under during your time at Woods Bagot. How have user-behaviour models influenced Woods Bagot’s current architectural design philosophy?

RD: At the same time as we are seeing a massive shift in the focus towards understanding user behaviour (and experience), we have arrived in the era of ubiquitous data. The key challenge now is how to access and process this data to elevate our understanding of what drives behaviour, and how we can design in a way that is more effective in predicting the behaviour of the building’s users. That is, design the building so it more accurately meets the needs of the users and how they will be inclined to use the spaces.

Where these are in harmony (the spatial characteristics and the users’ needs), the performance of the building will be improved.

Designers have been challenged with this in the past, and success in the operation of buildings has often been patchy, however beautiful the commentators of the day have said the building was.

We built the capacity of the firm’s team undertaking data analytics and computational modelling to vastly elevate the capability to get it increasingly right for the clients of Woods Bagot. This is the “Superspace” team.

The fact that the different sectors are blurring in their previously distinctive user requirements means that the modelling typologies emerging from the computational analysis is also blurring. We are calling these “Supertypologies,” which relate more to scale than building functionality.

In the end, performance is everything.

THE FUTURE OF PRACTICE

SN: What further influences do you envision SuperSpace to have on Woods Bagot projects in the foreseeable future?

RD: Within three to five years at the outside, we foresee that computational modelling will be at the centre of all the work of Woods Bagot. The design decision-making process will be much less about “opinion” and much more about evidence, and this evidence will comprise substantial data that has been modelled, increasingly in an algorithmic format.

We are entering an era where architecture will be empowered by an evidence-based scientific process, where performance is effectively modelled virtually before it is constructed. We have never had a period where the profession had access to such tools.

Investing seriously in this realm is essential.

"We are entering an era where architecture will be

empowered by an evidence-based scientific process,

where performance is effectively modelled virtually

before it is constructed. We have never had a period

where the profession had access to such tools."

– Ross Donaldson

PROJECTS

SN: In the last, say, 20 years, what would you say have been Woods Bagot’s milestone projects? Please explain how each of these projects has added to the practice’s already considerable legacy. If applicable, could you also tell us how the prevailing social theories of those times made these projects especially relevant?

RD: These projects, all in Australia, represented a new era in the scale of commercial architecture for the practice. Though not particularly notable for their innovation in their interior workplace programme, they were sound in their commercially modern design—and are significant as architectural commissions because of the calibre of the clients. [See image below.]

The College of the North Atlantic, Qatar Technical University in Doha was completed in 2005. This project was indicative of a new conversation within the practice about context-sourced design inspiration, generating a narrative that brought a locally sourced design rationale. It was the first Woods Bagot education project of scale, and it was exemplified the practice’s newly international focus.

The unfinished Nakheel Tower (previously called Al Burj Dubai) in Dubai, United Arab Emirates and 10 Trinity Square in London both represent a new phase in the practice’s evolution, being at the pinnacle of projects on offer in their markets at the time. The Nakheel project remains the tallest building that has ever started construction. It was variously designed to be 1-km, 1.2-km, and even 1.4-km tall. Construction had began on the massive footings and proceeded for over a year before the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 and resulting cash flow problems brought the project to a standstill. Nevertheless, Woods Bagot’s submission won against the very best and most qualified international competition. Ten Trinity Square, facing the Tower of London, was one of the more prominent heritage buildings available for development at the time and has produced some of the most exclusive residential apartments in the City, a Four Seasons Property.

There are now over thirty projects of significance under construction in China, in itself indicative of a new era of the development of the practice in the Asia region over the last decade, particularly the last five to six years.

Another indicator of the transformation of the firm is its list of the largest global clients, such as Apple, Google, and Greenland.

The size of the firm has grown six times more in the last decade. The Australian region has grown around three times, and the northern hemisphere around twenty—North America is now the fastest-growing part of the practice. ![]()