Could more green spaces in Shanghai, a city that has become the terminus of dramatic urban migration, help nurture newly formed communities? Simply put, could more trees help its long-standing, as well as its more recent residents, feel more connected? The yield of the urban forest is measurable.

The last decade has seen cities around the world invest in landscaping and tree planting programs of impressive scales. [Image above from HASSELL: Nanjing Tangshan Geopark Museum, China.]

In New York City, for example, the government offers services that actively drive the planting and maintenance of the city's five million trees located throughout its parks, streets, playgrounds, and backyards.

This "urban forest" generates measurable and much-discussed benefits. New York City says that its trees soak up one million tonnes of carbon dioxide and three billion litres of stormwater, provide habitat to countless birds and animals, and increase property values in the city by more than ten percent each year.

EACH DOLLAR SPENT ON PLANTING AND MAINTAINING

A TREE IN NEW YORK CITY PROVIDES MORE THAN

FIVE DOLLARS WORTH OF BENEFITS TO THE CITY.

China's changing landscapes

China's rapid urbanisation, unprecedented anywhere in the world, means that by 2030, another three hundred million people will be living in its cities.

Urbanisation is occuring at the expense of air and water quality, and limiting residents' access to natural environments.

Even older and comparatively greener cities such as Shanghai are recognising the need to improve the quantity and quality of the green space available to their residents.

shift in modern history,” says HASSELL Principal Richard Mullane.

“In a very small space of time, China has moved from a rural

society to an urban one."

HASSELL Principal Richard Mullane has explained what this means for China's urban planners. With a rising middle class and a generation of people who are demanding more from their cities, liveability is an increasingly important factor in their decisions.

China's city governments are recognising that they need to be tackling the issues arising from rapid urbanisation today to remain competitive and liveable in the future.

NATURE PLAYS AN IMPORTANT ROLE IN CHINESE CULTURE

AS A SOURCE OF INSPIRATION FOR WISDOM.

TREES ARE METAPHORS FOR RIGHTEOUSNESS, LONGEVITY, AND NURTURING.

How does nature connect to liveability?

Revisiting the earlier case study, researchers have found that each dollar spent planting and maintaining a tree in New York City generates more than five dollars worth of benefits.

But equally compelling is the less quantifiable value of landscape in the city. What personal benefit does it have? Do city dwellers form an emotional connection with their leafy neighbours?

In the distinct context of China, the dramatic immigration to cities there poses a different set of questions: could green places help nurture newly formed communities? Could more trees help people feel more connected?

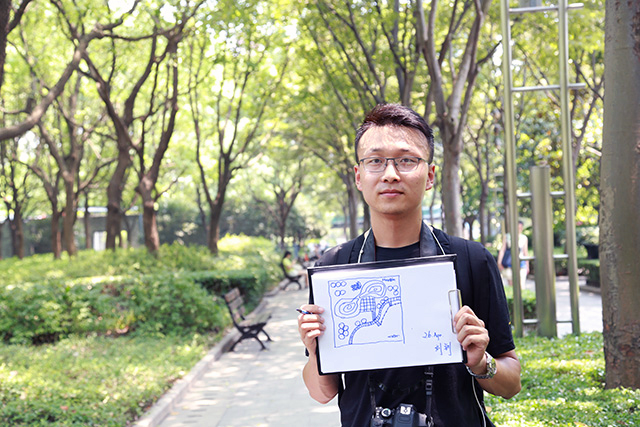

To explore these questions, we partnered with global insights agency, Flamingo, to undertake field research in the city of Shanghai. We surveyed Shanghai's residents to find out how they felt about nature in their city, engaging with people in their streets, parks, neighbourhoods, homes, and online through a comprehensive WeChat survey.

THE PLANE TREES OF SHANGHAI'S HISTORIC FORMER

FRENCH CONCESSION AREA ARE ICONIC SYMBOLS OF THE CITY,

LIKE THE BUND WATERFRONT OR THE PUDONG SKYLINE.

We found that nature has always played an important role in Chinese culture, as a source of inspiration for Chinese wisdom. Trees themselves are metaphors for righteousness, longevity and nurturing.

They also play a central role in the identity of Shanghai. The plane trees of the historic Former French Concession area are iconic symbols of the city, like The Bund waterfront or the gleaming forest of skyscrapers that comprise the Pudong skyline.

These hybrid platane hispanica—referred to as French Plane trees in China (faguo wutong—法国梧桐)—were planted from 1902, and remain central to the identity of these historical Shanghai neighbourhoods today.

“WHEN PEOPLE ARE LIVING IN A FRIENDLY

AND HARMONIOUS ENVIRONMENT, THEY ARE

MORE OPEN TO EACH OTHER.” – Shanghai resident

Shanghai stories—what people told us

The majority of people we talked to had concerns with the quality and accessibility of public space in the city.

- 87 percent thought Shanghai wasn’t green enough.

- 80 percent worried about air pollution.

- 61 percent wanted better access to nature.

- Only 10 percent of people could name a city park that made them feel connected to nature.

Over a third of the people surveyed chose leafy Ferguson Lane as one of their favourite places in Shanghai, and the place in the city that they most closely associate with nature. “This is one of the most beautiful places in Shanghai and walking under the canopy makes me feel so relaxed,” said one of the participants surveyed.

“SHANGHAI OFTEN FEELS INAUTHENTIC,

OVERLY PLANNED, AND CONTROLLED,

LIKE A STAGE SET.” – Shanghai resident

We also found some consistent themes:

- De-cocooning: as Shanghai continues to grow, green space was seen as an escape from the urbanity and congestion of the city.

- Variety: parks offer Shanghai's residents a great variety of constant change but at a natural pace.

- Simple happiness:many people are craving simple, unpretentious relaxation, away from the rat race.

- Health: the physical, mental and emotional health benefits of access to nature rate highly.

- Interaction: respondents felt that it was trees and nature that made human interactions and meetings feel natural.

- Wild and natural: people want access to greenery that feels dense, wild and natural.

- Immersive: people want an immersive escape from the city, places that feel casual and authentic and make interaction easy and enjoyable.

“IT'S GREAT TO DO SOME EXERCISE OUTDOORS

AROUND 8 OR 9 IN THE MORNING

WHEN IT'S NOT SO HOT IN SUMMER” – Shanghai resident

How can design bring nature back into the Chinese city?

Insights like these inform our projects in China, where we have been working both to preserve the surrounding natural environments of cities like Shanghai and Nanjing, and to bring nature back into the landscapes of these cities.

Our urban renewal project with the Hongkou District on North Bund will reconnect sites along the waterfront to give residents and visitors access to the water and connected parklands.

For Shanghai, we proposed planting two million trees for each one of the city’s children. The Huangpu East Bank Urban Forest would be a significant legacy for Shanghai, a major shift in the ecological and social functioning of the city and a place of endless delight and discovery for the people who live in it.

Creating and preserving these environments in China’s cities will enable people to reconnect with the nature that they crave. And it’s this layer of liveability that’s critical to the success of cities like Shanghai in attracting and retaining people from across China and the world.

This article was reprinted in its entirety from HASSELL. Read the original article here.