TIME Magazine proclaimed it “the chair of the century.” The backstory behind one of modern design’s most recognizable pieces of furniture is as fascinating as the reverence it still inspires 70 years after the first model rolled out of Herman Miller’s factory.

First, a misconception must be set straight: as brilliant as he was, Charles Eames did not singlehandedly design this icon. In truth, like all famed Eames designs, the chair could never have been made without a lifelong collaboration with his wife Ray.

The proposal

In 1941, Charles was a 34-year-old divorcé. Years earlier, the architecture school dropout had somehow managed to establish his own architectural practice, but was now busy attempting to reinvent the very concept of a chair with his friend Eero Saarinen at the Organic Furniture Competition sponsored by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. With the assistance of Berniece “Ray” Kaiser, a painter, Charles and Eero won the top prize.

Their victorious plywood chair design, however, could not be mass-produced as currently constructed. It splintered at the point where the back met the seat, frustrating their stated design intent of moulding a single piece of plywood into the shape of a fully functional chair.

Eero, dispirited, eventually gave up. Meanwhile, Charles asked for Ray’s hand in marriage in a handwritten letter:

Dear Miss Kaiser,

I am 34 (almost) years old, single (again) and broke. I love you very much and would like to

marry you very very soon. I cannot promise to support us very well—but if given the chance

I'll sure in hell try—soon means very soon. What is the size of [your ring] finger?

Ray answered yes, and the newlyweds revived the plywood moulding project, understanding that their financial security was dependent on the success—or failure—of the chair.

The prototypes

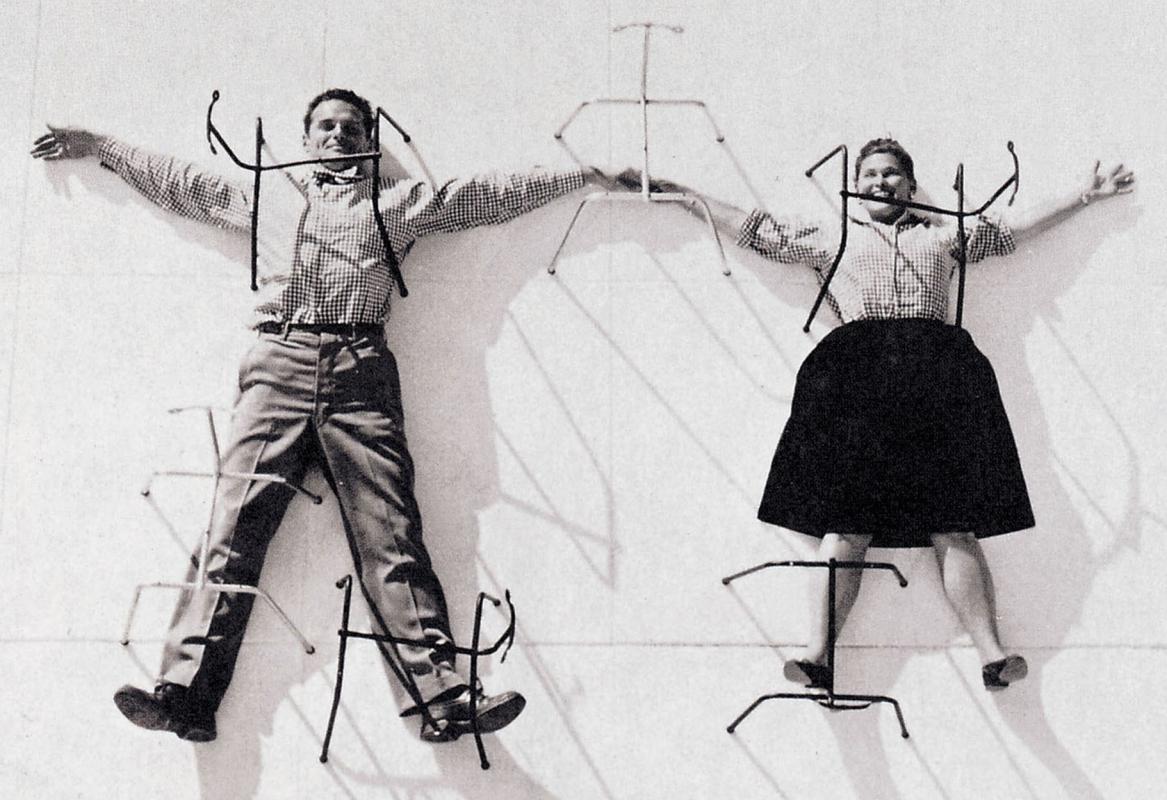

“I never gave up painting,” Ray said. “I just changed my palette.” Setting up a makeshift workshop in their apartment, Charles and Ray improvised their own moulding device, a crude contraption made out of heating coils and a bicycle pump.

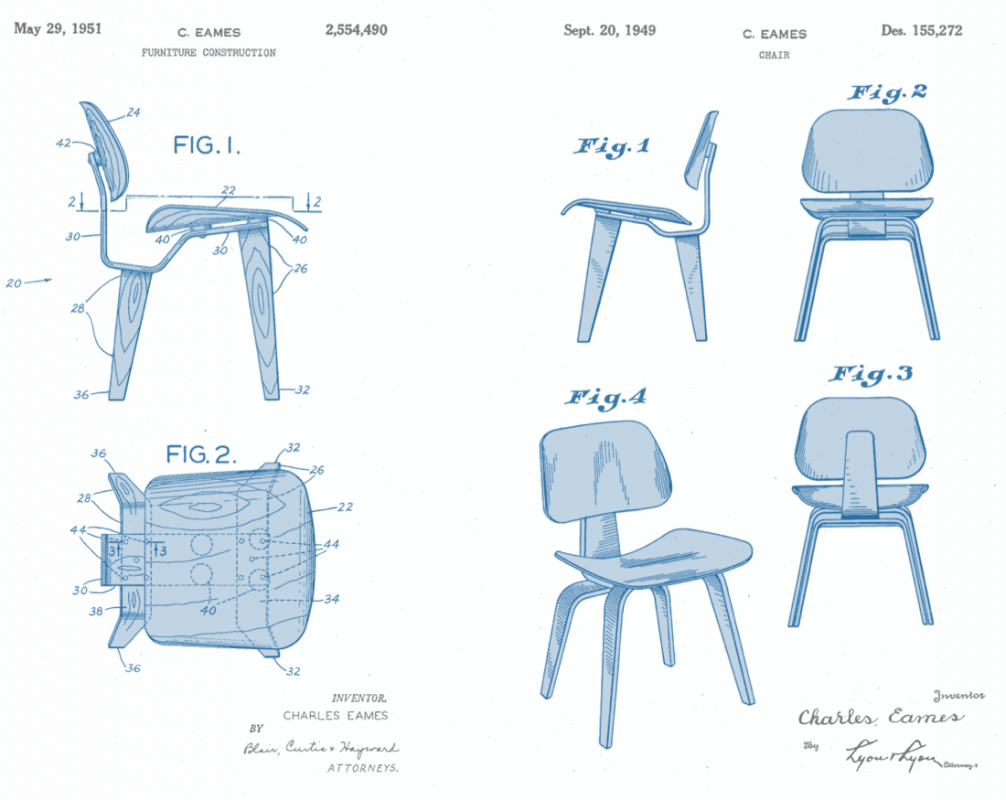

After much trial and error, the couple agreed to discard Charles’s original single-plywood-shell idea. Instead, a plywood spine linked the now separate seat and backrest panels. Reversing course, all the fastened joints were made intentionally conspicuous, which in retrospect added to the candour of the design.

Four heavy-duty black rubber washers affixed under nuts, later called “shock mounts,” braced the chair and isolated vibration. “The details are not details,” said Charles. “They make the product.”

The husband and wife’s final design intrigued Herman Miller, who put the chair into production in 1946—it sold for US$25 each.

LCW, achieved after so much

painstaking trial and error.

The accolades he received as the Next Great American Designer often embarrassed Charles because only he fully understood Ray’s crucial contribution to the design process. (The gender politics of those days dictated that a woman’s place was in the home.) “Anything I can do, Ray can do better,” Charles admitted.

Legacy

To this day, only Herman Miller and Vitra are licenced by the Eames estate to manufacture the late couple’s furniture designs, and the LCW remains a venerable bestseller for both companies. After the hardship that followed World War II, plywood was considered the affordable choice of the common man intent on rebuilding his life, yet Charles and Kay created among the most replicated pieces of furniture of all time out of this humble material.

“Art is the way you do your work, a result of your attitude toward it. Design is a full-time job,” said Charles. Living this philosophy, Charles and Ray Eames paid no heed to daily obstacles, got their hands dirty, and designed a sublimely beautiful chair, simple and honest, that has been copied time and again but never surpassed. ![]()