"There is nothing more poetic and terrible than the skyscrapers' battle with the heavens that cover them." – Federico Garcia Lorca, poet and playwright

Few architectural typologies polarize opinion as much as the skyscraper. Some believe it trespasses on the horizon; many, however, consider it a progressive fulfillment (and technological expression) of mankind's potential.

In New York, often thought as being the most vertical metropolis in the world (that distinction actually belongs to Hong Kong by a large margin), there is even the Skyscraper Museum, a homage that "celebrates the City's rich architectural heritage and examines the historical forces and individuals that have shaped its successive skylines."

There is some contention about how a skyscraper should be defined. Emporis, often cited as the authority on global building data, stipulates that a skyscraper should be "a multi-story building whose architectural height is at least 100 metres." Loosely, buildings over that height are designated as "Supertall" while those beyond 600 metres as "Megatall."

While the development of steel frames was crucial to increasing the vertical possibilities of buildings, equally important was the invention of elevators in 1857 by Elisha Otis, which not only provided safe and efficient people movement but also changed the pricing dynamic, with the upper floors now the most desired and expensive ones. Previously, the ground floor of buildings were the priciest, since climbing flights of stairs was, quite understandably, considered undesirable by tenants.

Skyscrapers tended to be built in cities with limited land area, such as New York and Chicago, although Melbourne, which was undergoing a land boom at the time, contributed several early skyscrapers, too, most notably the 51-m APA Building completed in 1889 in the Queen Ann revival style of English Baroque architecture. Building height rules in London, as well as aesthetics complaints from Queen Victoria, limited the construction of skyscrapers in that city.

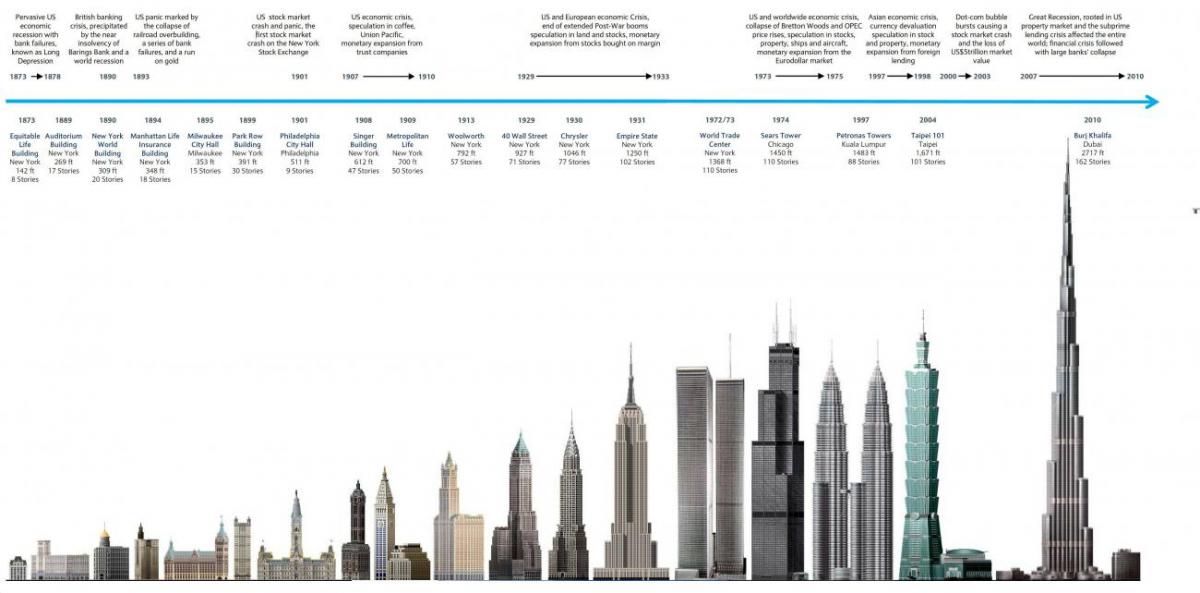

The main protagonists, therefore, in the tallest-building race were the cities of New York and Chicago, as evidenced by the list below of the tallest skyscrapers during the late-19th century.

- 1884–1890: Home Insurance Building Chicago 42 metres

- 1890–1894: New York World Building New York 94 metres

- 1894–1895: Manhattan Life Insurance Building New York 100 metres

- 1895–1899: Milwaukee City Hall Milwaukee 108 metres

- 1899–1901: Park Row Building New York 119 metres

Arguably still the most iconic skyscraper in the world is the 102-storey, Art Deco-style Empire State Building. Completed in 1931, its 381-m height (including the antenna spire) stood as the record for almost 40 years.

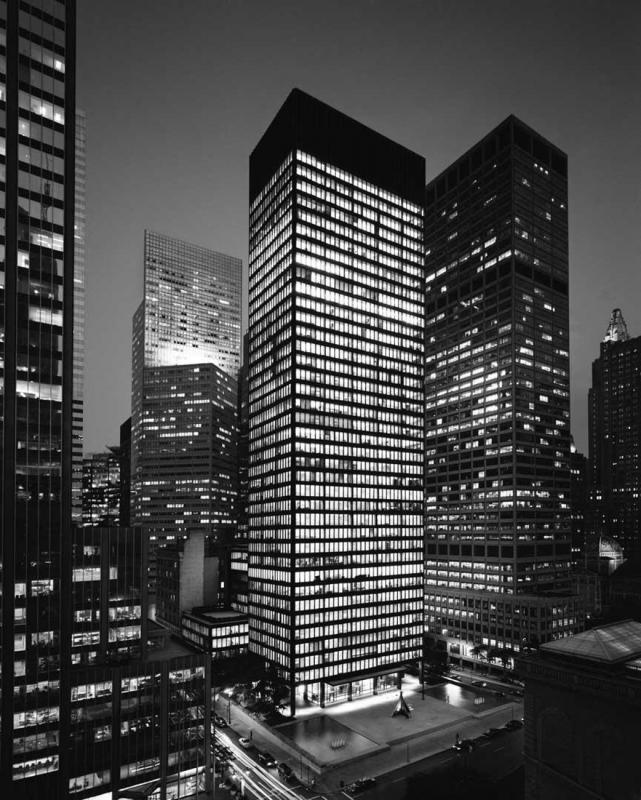

After World War II, skyscraper architecture embraced the International Style (rectilinear forms, plane surfaces that were stripped of ornamentation, and a still prevalent glass-and-steel combination). The Seagram Building in New York is a prominent example.

From the 1960s onward, innovations such as the "tube" structural system resulted in skyscrapers that were not just taller but also more diversely shaped. From 1996–2010, tallest-building narcissism peaked, with bragging rights being claimed at an average of less than every three years—first, by The Petronas Towers (Kuala Lumpur) then by the International Finance Centre (Hong Kong), Taipei 101, the Shanghai World Financial Center, and Burj Khalifa (Dubai).

The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, an international non-profit body specializing in the field of tall buildings and sustainable urban design, has coined the term "vanity height," the distance between a skyscraper's highest occupiable floor and its architectural tip (including spires but not antennae, signage, flagpoles, and other functional extensions). In its report, the CTBUH states that not only is the 828-m Burj Khalifa completed in 2010 currently the tallest building in the world, it is also the "vainest" because of its 244-m non-occupiable vanity height.

Expected to be completed in 2019, the 189-storey Azerbaijan Tower within a development of artificial islands near the city of Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, is the tallest building in the world currently under construction (at least until the next one inevitably comes along), with a projected height of over one kilometer. The simplistic "height is might" skyscraper typology is being challenged by a growing number of influential architects.

Contemporary skyscrapers have matured into more mixed typologies wherein office, residential, retail, and lifestyle spaces are now vertically integrated to accomplish today's all-embracing architectural programmes. Once, skyscrapers were put to use only during a fraction of the calendar year—its lights dimmed after office hours, as well as during weekends and holidays. Nowadays, though, they are mini-communities that hum with activity all throughout the day and night.

"Two World Trade is almost like a vertical village of bespoke buildings within the building, that also can be seen as a single tower," explains Bjarke Ingels, founder of BIG, of his skyscraper in the reborn New York site of the infamous September 11 terrorist attack. "It's ok that the building's components have different proportions, and are then stacked on top of each other. … It feels like it's a completely straightforward tower, but then there's something weird going on."

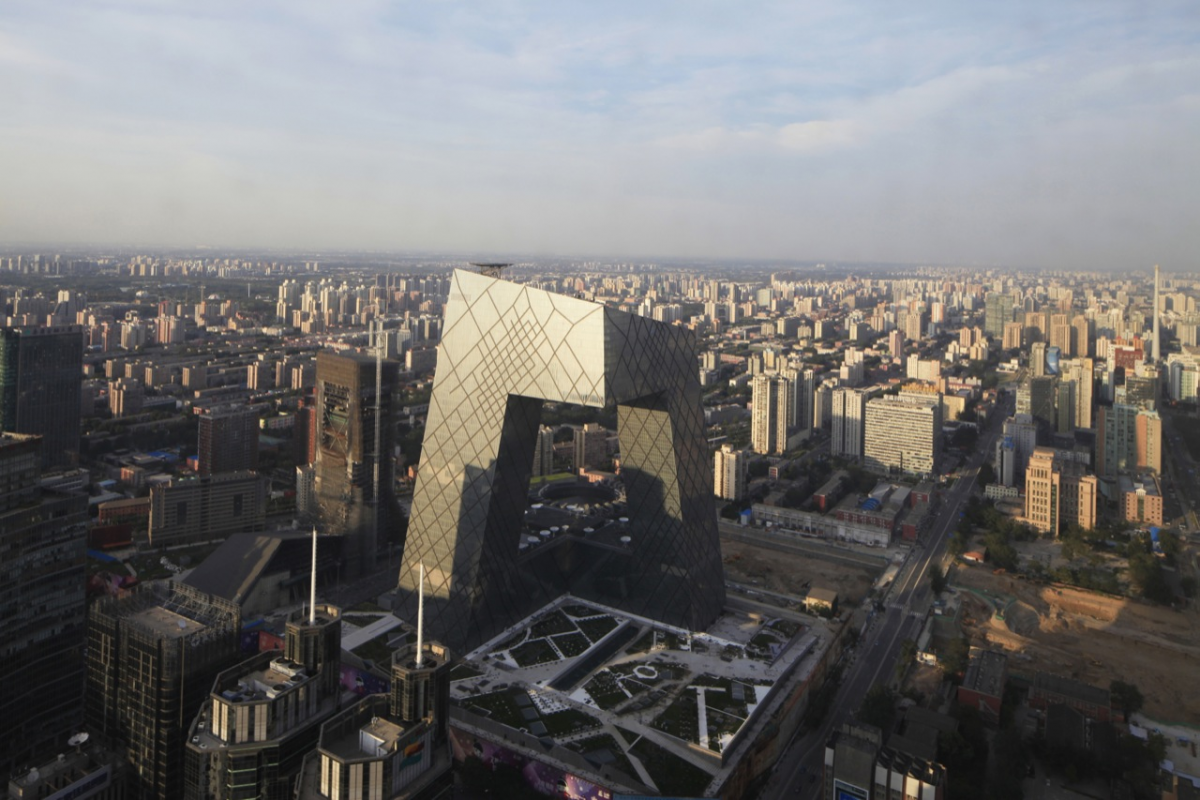

Said Rem Koolhass after winning the CTBUH "Best Tall Building Worldwide" award for OMA's CCTV Headquarters in Beijing, China, two years ago: "I didn't think there was a lot of creative life left in skyscrapers. Therefore, I tried to launch a campaign against the skyscraper in its more uninspired form." CTBUH describes the building as having "single-handedly paved the way from the height-obsessed, set-back skyscraper of the past to the sculptural and spatial skyscraper of the present, at the scale of the urban skyline."

The skyscraper's form is progressively being redefined. While "Supertall" and "Megatall" buildings are evidently here to stay (not just because of vainglory but also because of urban-density issues), very interesting typology debates are being posed these days by freethinking architects about past aesthetics and the very utility of these mighty structures. ![]()