We sat down with Bogusław Barnaś, who founded BXBstudio in 2009 after working for a number of internationally known practices, including Foster + Partners, MAKE Architects, and Ingarden & Ewy Architekci. His studio was one of 20 practices included in the Wallpaper* Architects Directory 2014, "an index of the world's best young architectural talent." In the same year, the architect, designer, and academic also won a World Architecture Award for his One Tree House.

His professional experience includes work on projects of varying scales ranging from family houses to groundbreaking icons such as The Walbrook office building in London, UK (Foster + Partners); the competition-winning headquarters building for fashion brand ESPRIT edc in Ratingen, Germany (MAKE Architects); and the Museum of Polish History in Warsaw, Poland (Ingarden & Ewy Architects in cooperation with Arata Isozaki, Japan), among others. Read below as he explains his influences and shares fascinating insights about the globalization of architecture.

STEVE M. NAPIER: Why did you become an architect?

BOGUSŁAW BARNAŚ: I think the story starts from my childhood when I was drawing and drawing. I was really very young. In the beginning, I was drawing a lot of cars, but I also painted, and in school I started to think about how to use my drawing skills in the future. Then came the idea to become an architect—more of an architect than an artist because I was very good with technical things like Physics and Mathematics. It seemed very good to connect both of these elements.

SMN: You connect Physics and Mathematics to being able to draw art, which is actually quite an interesting combination because they seem so opposite. It is a very unique talent to have. Did you have a passion for the built environment and for how people live and work and move?

BB: I think this kind of question is directly connected to architecture and creating space. I think it came when I was studying architecture. Before, I had more passion about aesthetics, beauty, drawing, and art, but it was not really about creating space or environments for people. I actually got the passion for architecture when I studied it.

SMN: How many studios did you work for before you started your own?

BB: The first one was a very small practice in London, and it was for a very short time. I really wanted to work for Foster + Partners. This was my dream starting in the second year at university. When I decided to go to London, I had already sent a portfolio to Foster + Partners, but I did not receive a reply. When I was already in London, I started to work for a little studio company designing houses. I sent my application again, and I was invited to work for Foster + Partners. It was my second studio. After Foster + Partners, I joined MAKE Architects.

Actually, these two studios are very similar. MAKE is a continuation of Foster + Partners because it was established by Ken Shuttleworth, who was a senior partner at Foster + Partners. Seventy percent of the people from MAKE Architects were from Foster + Partners, so it was really like another Foster + Partners studio.

SMN: What was it about Foster + Partners, their studio or architecture, that made you want to go work for them?

BB: I can say that Foster + Partners is something like a university more than a place to work because it is a big community with a lot of young graduates. It has a lot of clever senior partners, such as professors from Germany, from the United Kingdom. There are a lot of people from the A.A. [Architectural Association School of Architecture] and the Bartlett School of Architecture. For me, the time at Foster + Partners was like an extension of university. There were a lot of lectures at around 7 p.m. After work, you could go listen to a lecture or presentations from other teams.

Foster + Partners is like a lot of studios in one. For example, I was working with a team of fifteen people, and we were like one office, one studio. Next to us in the open space was another studio, so you can learn from each other. It was not just work. I used to stay in the studio until 10 p.m. because I was learning. It was just an amazing time. Later, I came back to Poland, and there was one of the best studios on Poland called Ingarden & Ewy Architects.

SMN: So regarding your time at Foster + Partners and at MAKE Architects, how did your views on architecture change? How did it influence you?

BB: I think that during every period of change, I get some fresh attitude and a new vision for architecture. For example, Krakow University is more artistic, and it is more like A.A. Functionally, it is very strict—and maybe “technical” is not the right word—but real. At Fachhochschule Münster [Münster University of Applied Sciences] in Germany, it was very logical. I was studying with Julia Bolles-Wilson in Germany, and she has a lot of wisdom and knowledge in architecture. [Julia is a partner at BOLLES+WILSON]

If you look at the projects of BOLLES+WILSON, their architecture comes from the functional and economic expectations of the client. When I started designing in Germany, I was a little bit of a Coop Himmelb(l)au designer, and she was really unhappy with this! I had a passion for Coop Himmelb(l)au at this time, a very controversial way of designing. Julia Bolles-Wilson was really against this kind of designing because with Coop Himmelb(l)au, form does not follow function, but form is in the first place. The form is crazy, and you try to put the logic of function to fit with a crazy form.

SMN: What you were first saying about Coop Himmelb(l)au, it focuses on the form, and then the function, so the form of the building is shaped around the function. That is what Patrik Schumacher in his theory says about Parametricism, and the way he designs is he creates forms, and those forms very much are built and formed by the program and function of each building.

BB: Is this program connected to the function, or more to the form?

SMN: It is the function.

BB: Because I sometimes have the feeling that [the work of] Zahi Hadid is more of a product design. Sometimes I am not convinced that all the buildings are architecture. It is like a sculpture, it is like designing a beautiful shape or sculpture, and not really form from function.

SMN: When it comes to a client actually approaching you, what are the key things that actually drives you when you answer and come up with concepts and solutions?

BB: At my stage, it seems to really still be developing, and first of all, I can say that in my experiences with the likes of Krakow University, Foster + Partners, MAKE Architects, and my own studio, I try to make the connection when I design something in Poland with the Polish vernacular. This firstly comes from Foster + Partners and my experience in Great Britain, but with [contemporary] architecture there is too much globalization, and architecture has become homogenous.

SMN: Yes, I know what you are saying, the vernacular is somewhat disappearing.

BB: As an example, you can imagine if you work for Foster + Partners, you design a building with your team, but there are fifteen people, and each person is from a different country. It means that there is a global influence in the way of designing. I found that British architecture, especially in London, is very global and not linked to something very special.

SMN: Which I suppose is the big question, if we talk about London right now—is it is losing its local character? It is becoming a city full of glass. It doesn't taste like London anymore.

BB: It is like a big capital, like Hong Kong or Taiwan. I don't really feel good in this kind of globalization, even in districts like London where you really feel like you are in England.

SMN: I suppose that is what made your work stand out for me. I look at a lot of architectural concepts for competitions and so on, and I have become very bored with them because it is so globalized. I see that you understand the sense of place in your concepts.

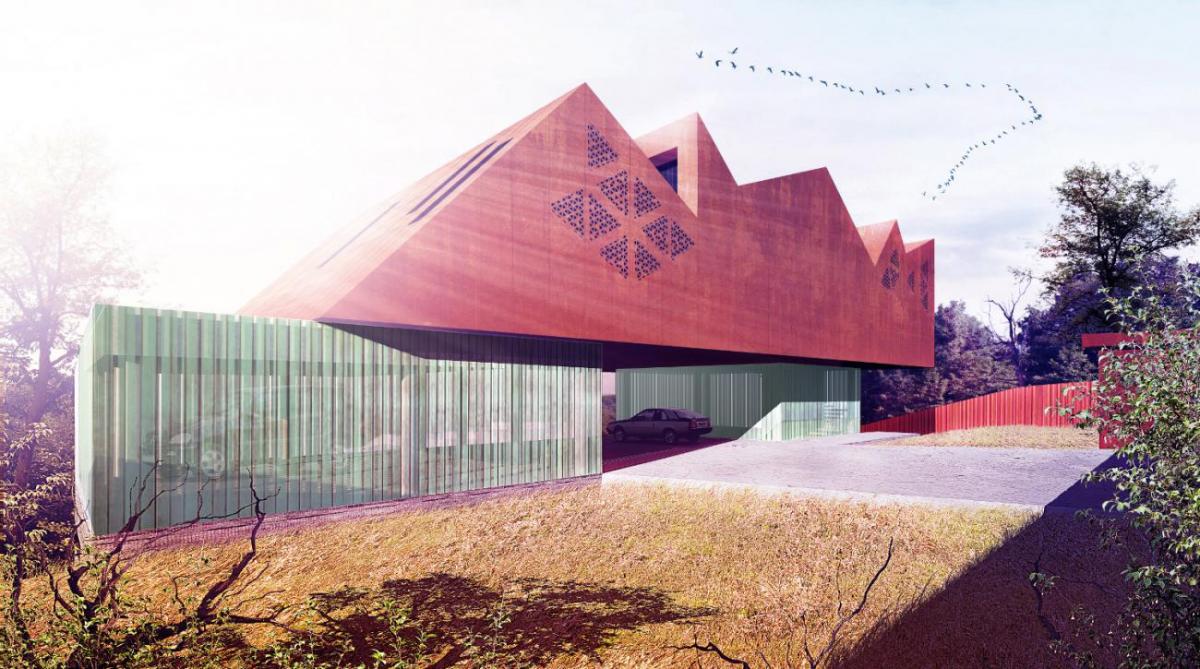

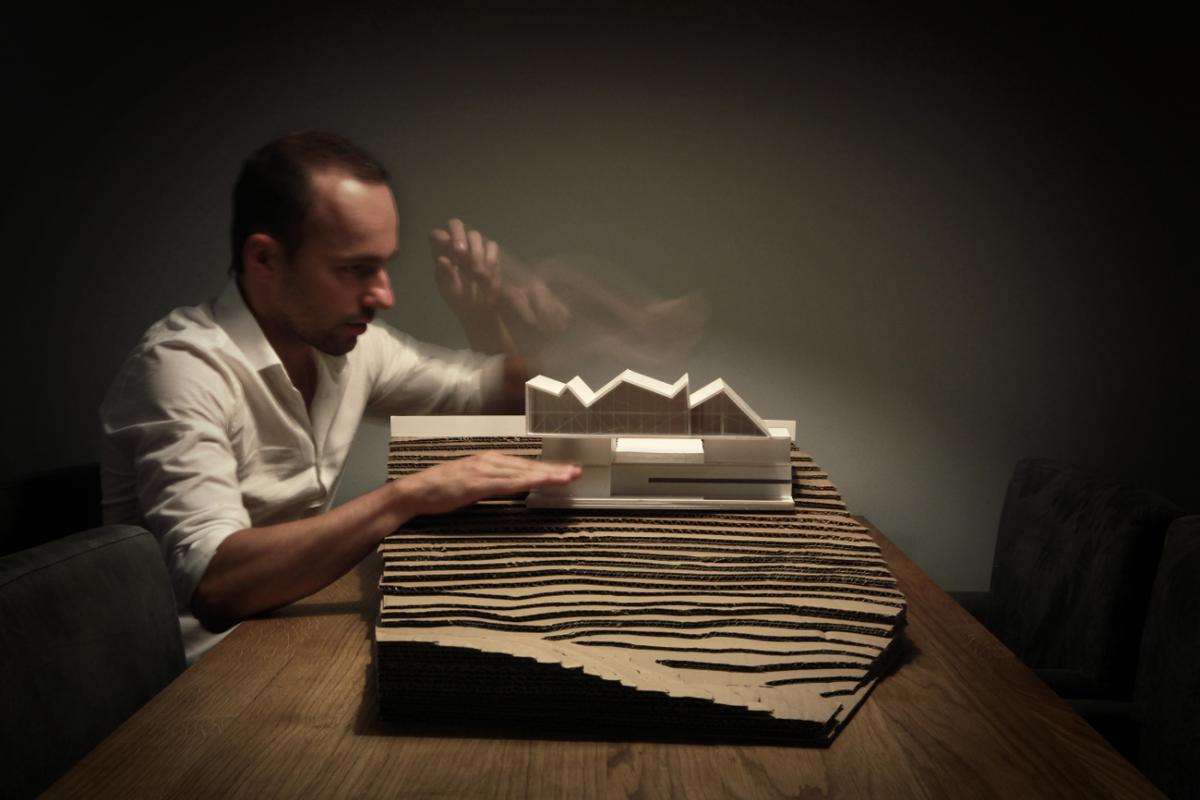

BB: For competitions, we spend a lot of time researching the country when we are designing it, the mentality and the tradition. We were designing the Bamiyan Cultural Center in Afghanistan, and we tried to catch the local tradition and the building environment. I do it, and I found that I do not like the global, big studios. Of course, there are some projects that are from Foster + Partners that really links to the local, but many times it is global architecture.

SMN: I see a similarity between you and Peter Zumthor in that he understands sense of place. To me this is very evident in your work. How does nature influence your design?

BB: We really try to connect to the landscape, nature, and mountains in the area, especially designing a lot of houses. I think of nature—the conditions like sun, rain, and wind. Pollution, as well.

SMN: Sometimes I feel a lot of buildings and houses, especially in the United States, are designed by 3D concepts and renders. The houses are designed and presented to the client, and it is almost as if the house should almost be perfect, and it should look like the renders for the next fifty years. To me, the buildings that you design are almost designed to age gracefully, to age beautifully. They are designed to look lovely on day one, but also to be beautiful even after seventy years. They’re almost designed to age gracefully.

BB: I hope so!

SMN: I think that has to do with you understanding the sense of place, looking at what the local fabric is, what they use for different materials, and actually linking it in and saying “This is what they used a hundred years ago in terms of different types of materials, geometries, and architectures in general, but it looks good now, so there is no reason it won't look good in another fifty years.”

BB: I think this gives you this security, as well. A good example would be this Bamiyan Cultural Center, a museum in Afghanistan where we just used the bricks from the locals. This will always fit the landscape. We just use a very easy and simple module like a couple, the roof with the arc. It was created by a local yellow-coloured brick, and it was very simple. It was one element because we used local material and a very cheap structure. It will look well, even if you don't care about the maintenance of the building because brick is not glass. You do not have to clean it all the time. ![]()