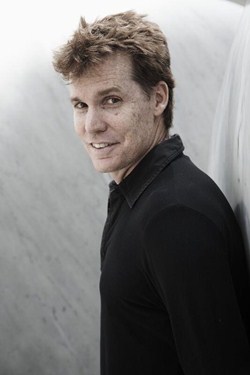

Ken McBryde is a Principal at HASSELL and a design leader at the Sydney studio. Drawn to complex design challenges that demand innovation, he is also driven by a strong commitment to social and environmental sustainability. The self-confessed “architect of adventure” is consumed by the theory and execution of sustainability and materials technology. Here, he talks about about his stalled motorcycle racing career, how one particular building in Paris convinced him to become an architect, and the influence of Pritzker Prize-winner Renzo Piano.

STEVE NAPIER: The Pompidou Centre in Paris, with its sculptural, structural elements and long-span beams on the outside of the building, is by Renzo Piano & Richard Rogers, and you once worked with Renzo Piano Building Workshop...

KEN MCBRYDE: There are a couple of very good ideas in the Pompidou Center, to start with, about people. What those young guys did was save half the site for placemaking. The piazza in front of that building is one of its biggest successes. What I’m talking about is the setting up a gathering space, a public space for performance in the city—the active entry facade, with its external circulation path, is its backdrop.

Look at the activities and the sloping piazza in front of the building. They reserved half the site, they went higher, and pressed the programme into a smaller footprint so they could get a large public gathering space. Absolutely a winning move.

The second thing they did was turn the art industry inside out. Up until then, you had buildings like the Louvre and the like, which were stately and intimidating institutions. They turned that elitist paradigm inside out. They put the circulation on the outside and made it a tourist attraction. You can discover art there by accident. You can traverse your way up, enjoying Paris, and you see inside the galleries as you go up, and you go, wow, let’s go in there. You don’t have to intentionally go to some particular exhibition; you find it by chance. You get curious, and you go in. It’s brilliant.

The other thing is that it was highly provocative in its day, deemed to be ugly and shocking, but it’s an example of what I was talking about earlier. I learned this from my dad, who restored really old motorcycles and understood every spring, nut, bolt, every component of old motorcycles, and he saw beauty in them. I realized that as a young kid. That’s why I think Parisians came to love the Pompidou Centre, which offended them at first. They have come to understand how it works.

That building expresses how it works. Like the structural cantilever action, those beautiful cast arms called “gerberettes,” the tension pull-down, and the trussed beams create big clear spans for art to be installed, however you like, inside. Column-free space, services on the outside, completely free space.

Gallery theory has moved on a lot since then, but in its day it made a massive contribution to the way art is curated and how people think about art. It’s become a very well-loved building. That’s an example of a building that will stand the test of time. The Pompidou Centre is a building that works, and it’s driven by a concern for people and our natural curiosity.

On a personal note, I grew up in the country and didn’t even know what architects did—certainly had never met one or heard anyone use the term. When I saw that building, I decided I wanted to be one. Until then, I wanted to be a professional motorcycle racer.

SN: How did you come to work with Renzo Piano?

KM: I went to Europe to try to accelerate my motorcycle racing career. My mum tricked me into doing an architecture degree, which put my motorcycle racing on hold. By the time I finished, I was 26 years old, so pretty old for establishing a racing career. I decided that if I was going to make it in motorcycling, I had to go directly to Europe—but actually, I had absolutely no idea. I arrived—explored some awe-inspiring tracks like Monza and Hockenheimring. It was freezing cold; I had no connections; I was quite lost. So when I arrived in Paris, and visited the Pompidou Centre, I went, you know what, I think I want to be an architect.

I made a plan and went to London to get a highly-paid contract job and saved up 3000 pounds because I figured, to get a job with Renzo Piano, I’d probably have to work for free and prove myself. I had my student portfolio, which was kind of okay since I ended up with honours at uni. So after the two years of experience in London putting buildings together, I knew how to put buildings together because I’m a practical kind of guy.

I learned how to make things with my dad while restoring motorcycles—for example, like my 1954 motorcycle when I was 16. And racing. You learn how to push materials to their limit, but not beyond. This gave me had a sense of materials and how things go together. So I did get a job with Renzo in Paris, and to my surprise there was no question of working for free—I was well paid.

SN: Do you think a lot of architects generally aren’t practical people?

KM: Like in any industry, it takes all types. And thank heavens because I rely on incredibly intelligent people, very theoretical people. I rely on specialists. We bounce off each other. It’s great to have people who are less practical, and it’s also great to have people who are more practical. I guess I’m somewhere in-between. I have some crazy ideas that need to be pulled down to earth at times. Generally, with proper constructive teamwork we can work out a way to make great things happen.

Architecture is done by teams, including the client and consultants, and that whole team is going to be on that journey. At a certain point, the project actually guides the team. It gets its own life. If the ideas are strong enough, well-enough based on decent research, then the ideas become irrefutable and powerful. And then it becomes a question about whether the architect can actually explain those ideas and get the buy-in from the team. Once we have that, the project has its own momentum. Then, as an architect, it’s a question of what to let go and what to keep for that idea to be intact and improved upon at the end.

It’s an honour to build a building. It’s a great achievement to have one done, and it shouldn’t be squandered. It’s not something to take lightly. We’re obliged to make a positive contribution.

SN: How did Renzo Piano influence you, and what are your thoughts about his architecture?

KM: Renzo is the son of a builder, and a lot of his ideas lie in the way a building is made, and I relate to that. He describes himself as a humanist. He’s not trying try to do too much; he just tries to do what he does incredibly well and base it on really good ideas, really good intuition and observations.

lie in the way a building is made, and I relate to that."

Working with Renzo and Peter Rice and his Arup team, I learnt about true collaboration between us architects and our engineers—that we need to work very closely together from the very outset of a project. Certainly, as a young architect, I also learnt on Kansai International Airport, that you have to be able to lose a lot of what you hope to achieve, but it's a question of what.

Having what we call at HASSELL “conceptual clarity” guides what you can lose and what you cannot for the project to remain a success. If we handle these processes of so-called “value engineering” properly, the project can infact improve—yes, it becomes a little more frugal, yet it may also become more clear. Renzo refers to this necessary quality we architects need as “intelligent obstinance."

• An Interview with Ken McBryde, Part 1

• An Interview with Ken McBryde, Part 2

• An Interview with Ken McBryde, Part 4