Ken McBryde is a Principal at HASSELL and a design leader at the Sydney studio. Drawn to complex design challenges that demand innovation, he is also driven by a strong commitment to social and environmental sustainability. The self-confessed “architect of adventure” is consumed by the theory and execution of sustainability and materials technology. Here, he talks about his research-based approach to design and how urban density can still feel “generous.”

STEVE NAPIER: I understand you have been teaching and conducting research throughout your career. You have a Research Masters Degree in Architecture?

KEN MCBRYDE: Yes, after returning from six years of working in Europe, I wanted to practice architecture that was founded on a research approach. So I taught at University of Queensland, Queensland University of Technology, and Sydney University. Plus some guest crits at University of Technology Sydney and University of New South Wales. The teaching helped fund research. I undertook four years full-time Masters by Research looking into innovative prefabricated engineered timber for climatically appropriate housing in the tropics. I also acted as Research Assistant on Stephanie Smith’s Masters, measuring and recording the last remaining self-built aboriginal “tin camp,” Goodooga, Western New South Wales. [Topmost image: Ken McBryde presents Tanna Islanders the low-cost Category 5 "safe house," a half-local, half-prefab structure.]

St. Andrews Anglican Church over a period of six-and-a half years. They

experimented with ideas for a segmented portal system while

working for Renzo Piano in Italy.

What that taught me is an approach to design that is research based. At Renzo Piano Building Workshop, we used applied research techniques in an informal way also. But actually doing a formal Research Master's Degree in the days when it was like a pre-PhD, not just an architecture degree, taught me proper research methodology. I learned the more you ask questions and the deeper you dig, the more you unpack an issue, or the more thoroughly you interrogate a brief or project context—if you do that rigorously enough, valuable ideas will emerge.

SN: Can you give me an example?

KM: A PhD is an original contribution to a field of knowledge. A Masters by Research was defined by new combinations of knowledge. The process of that research is looking at what is being done and interrogating it more and more deeply until the original ideas drop out. And that's a very valid way to approach the design of a project.

It's a way of our ideas being truly valuable to a client, useful to a project. So, that's the way I try to approach design and design ideas in HASSELL, and it’s part of the design methodology we use and mentor our young designers with. In fact, there's a research stage that generates ideas for clients that are worthy, and those ideas are more likely to stick because they’re not based on a whim.

So yes, that four years of research and teaching was a very valuable deepening of my understanding of the design process. A really simple and commonly used example is digging into the history of a place to find valuable inspiration that informs design and, ultimately, the end users. But the research could also take you into materials, structure, social settings, or culture.

SN: Can you describe what is architecture?

KM: May I first respond by answering what my daughter, at five years old, told me what architects do: “Daddy, I know what architects do. They see things before they are there.”

To answer your question: architecture is an uplifting experience for pretty much all our senses—searching for a resonance of materiality, light, and shade; aromas; and the passage of time—a journey or experience moving through spaces. And I firmly believe enduring architecture and design is all about making places for people, making memorable and uplifting experiences for people that make a positive difference to their lives.

When our projects are city-making, it gets exciting. For example, I am lucky enough to be involved in the rejuvenation of Darling Harbour and Metro North West. The Metro, with trains every 4 minutes straight into town, will effortlessly connect people living in the North West growth corridors to the vibrancy of the city—people falling in love with cities and Darling Harbour Live is part of that.

SN: In the UK, there's talk at the moment about Peter and Alison Smithson and their Brutalism Movement, which many feel have failed. How can we know if the current architectural ideas won’t be seen as a failure in the future?

KM: I think a good place to start would be at a similar era in Holland, with Herman Hertzberger. His architecture might also be associated with the stripped-back, raw concrete and masonry materials of Brutalism, but he was preoccupied less on a visual style or expression. Hertzberger was absolutely people focused, and in a Dutch kind of way, it was tough-looking, raw architecture.

But when you get in and understand what he was exploring, it was all about transition spaces, in-between spaces, personal spaces and degrees of privacy, and understanding how people live and create a sense of community at home and in the workplace. I think you’ll find Hertzberger’s work is still highly relevant and highly respected today. Very few would consider it a failure.

Certainly, I still use it as a point of reference today. What he taught us is extraordinary. Both his commercial work and housing are still relevant today. Herzberger is not about style but about understanding the drivers around the human condition.

SN: What is your motivation? Because if you are egotistical, is your ego motivating you to create a beautiful building that seemingly fails because it hasn’t worked as a space for people?

KM: Absolutely risky… what we do in HASSELL to avoid that risk is test ideas for the project against a series of points of view or criteria. These are: Function, Context, Beauty, and Aspiration—in no particular order or priority, by the way. We will continue to test our work against those criteria at all stages of the project. What we are looking for is the overlap of all those criteria. We call that the “the sweet spot.”

Some projects will have more emphasis on one criterion or another—that's fine—as it may be driven by the clients’ particular aspirations or a functional concern, but somewhere there's a sweet spot to be found, and we wouldn't proceed with a line of thinking if our design ideas weren’t well researched and creating a well-evidenced “sweet spot.” This design process produces conceptual clarity based on worthy ideas.

SN: So for you as an architect, what fascinates and influences you? Moving forward, what is your focus as an architect? Are you fascinated, not just obviously by people in cities, but by a certain sector or type of building?

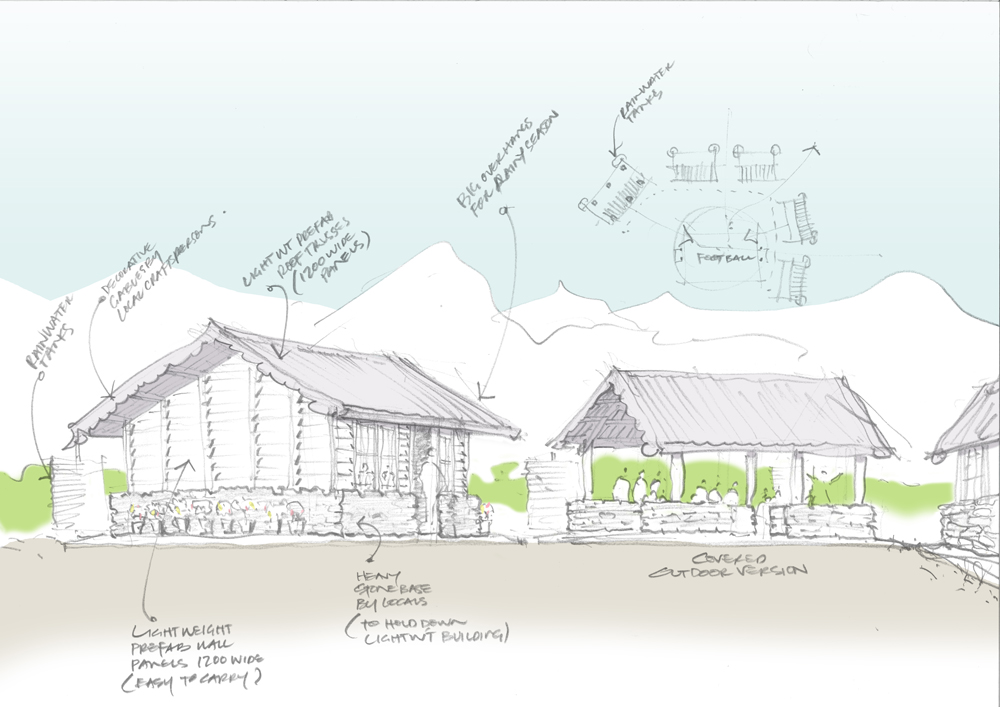

KM: The thing I care most about now is using my skills, knowledge, and experience to work on projects that will unlock the most potential in a place, condition, or material. And sometimes that can be in a place that generally doesn't benefit from the work of architects. We’ve just done a project in Nepal, for example, using lightweight prefabrication techniques to make earthquake-resistant schools for remote areas accessible only by foot.

Traditionally, the Nepalese use heavy construction, rocks piled on top of each other with some poor-quality concrete. This construction shakes to pieces in an earthquake because the mass of rock walls and concrete attract a lot of earthquake load. The lightweight cold-rolled kit system we designed with David Carolan of TTW has just been government approved. It’s taken quite some negotiation because it’s a completely different paradigm of construction to what they are used to. The architectural design, however, does have a direct connection to their local vernacular and has been warmly welcomed.

Traditionally, the Nepalese use heavy construction, rocks piled on top of each other with some poor-quality concrete. This construction shakes to pieces in an earthquake because the mass of rock walls and concrete attract a lot of earthquake load. The lightweight cold-rolled kit system we designed with David Carolan of TTW has just been government approved. It’s taken quite some negotiation because it’s a completely different paradigm of construction to what they are used to. The architectural design, however, does have a direct connection to their local vernacular and has been warmly welcomed.

For TTW Engineers and ourselves at HASSELL, the work we did was nothing particularly unusual from our point of view, but it sure is in Nepal. Providing well-designed schools in remote areas that act as safe houses during earthquake—that’s a great thing that we at HASSELL can easily do. I guess that's an example of applying contemporary technology and ideas sensitively into a cultural setting where we can make a big difference. And it could be anywhere, not necessarily in remote places.

I'm not trying to say that it's just those kind of projects, but I do like projects where the intelligence we bring, the thinking we bring, and the research outcomes we bring make the biggest difference. I am attracted to the clients who know that innovative thinking actually pays dividends. Not just commercial dividends, but long-term improvements in the human condition and our ecology.

SN: The interesting thing is that if you think of the commercial outcome first, you ultimately fail, not necessarily in the short-term. Mainly, if you are doing a large project in the city with a lot of people whose social outcomes are not considered in the long-term, it will fail miserably. You have to take generations of lives into consideration. Some of the most interesting architecture and concepts seem to come from architects who focus on low-budget work and who are indeed motivated by that social outcome. For example, German-trained architect Francis Kéré, who is originally from from Burkina Faso, Africa comes to mind.

KM: Oh, yes, I agree—that's truly beautiful and inspiring work. I am also super-encouraged that Alejandro Aravena has been awarded the Pritzker prize. His “half-house” ideas have had a big influence on our work for low-cost Category 5 cyclone-rated rural houses in Vanuatu. The pre-fab modular flat-pack kit we designed consists of a series of timber portal frames at 1.2 metres apart.

These frames can be filled in by the locals with woven sago, grasses, or bamboo. But we also supply wall panels from recycled plastic waste to create a Category 5 safe room within the portal frames. The families can shelter there during cyclones. The lightweight woven materials will of course blow away but cause no harm and can be replaced, as they typically do after cyclones.

If we jumped back into the city, then the thing that will be motivating us at HASSELL is how large projects contribute to the social fabric of the city. I was in New York in October presenting at the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat annual conference. In our session, the speakers were asked to talk about “designing global skylines,” and I said, ok, fine. Skylines look after themselves, that's an ego thing. How about we talk about groundlines?

I was asked to bring an Australian perspective to the session. I reflected on the fact that we have a vast country here, and our indigenous cousins navigated this expansive landscape through verbal descriptions—or “songlines,” as they have been called—handed from one language group to the next, describing how to traverse the countryside from notable landmark to landmark. As our cities become megacities, how will we successfully navigate them?

We often see the identifiable skyline, so what is it that navigates us through the fabric of the city? The projects we are being asked to do are generally getting bigger and bigger. How do they remain meaningful at the human scale—I think that is the social aspect again that should drive a project irrespective of its scale.

We enjoy engaging in healthy discussions with our clients about the commercial value of contributing generously to the social fabric of the city. They might believe, for example, that when we propose a laneway, or through-site link, it might be a loss of valuable retail space. We have to find the language and means to demonstrate the value of urban design, that contribution to groundlines, if you like. The themes or connections that take you through and draw you to explore the precinct or city.

SN: That is interesting because I was talking to Matt Lynch, head of research at Woods Bagot. I was speaking to him about the powers that govern a city’s tall buildings from going from singular to mixed use. What seems to be happening, actually, is that we are going back in time. Take, for example, the Melbourne suburb of Richmond, where you’ve got everything you need. Why would you leave? It really is a village as we once knew it. Maybe for these new villages to be more efficient and commercially viable, they need to go vertical to avoid an

urban sprawl.

KM: For two years, I was living in a very small space under the roof of a classic Parisian building at Place Bastille; I rarely cooked. Instead, I would go to cafes for breakfast near where I lived, and have lunch and dinner near the studio in the Marais. I quickly realised that while Paris is a very big city, it’s made up of a lot of very friendly little villages.

If you want it to feel like a big city, then you hit the town—you go to the Champs-Élysées or to the big nightclubs. But it wasn't long before my local cafe owners, fishmonger, butcher, and bakeries would call out to me as I went to work and say “hi.” Well, actually: “Bonjour, have a great day.” People knew each other and looked out for each other, and if you walked to work you would really feel like part of the fabric of the city. It was wonderful experience of belonging—finding your place in what is a very big city.

I just want to support your story by saying it was a series of mixed-use villages that adjoin each other, and the planners hadn’t deemed that any particular building was for any particular use. At the same time as being incredibly dense, that city also feels very generous.

“The Shard” in London by Renzo Piano Building Workshop is good example of this tendency now toward mixed-use towers. It’s very permeable around the ground plane and offers quite a few opportunities for the public to interface with the upper levels of the tower. Ideally, the occupants will feel part of a series of villages, in that case vertical. ![]()

Read the rest of the Ken McBryde interviews here:

• An Interview with Ken McBryde, Part 2

• An Interview with Ken McBryde, Part 3

* An Interview with Ken McBryde, Part 4