Have we reached the "smart" tipping point? Will cities master-planned with technology as the overriding design element be able to build genuine communities with an inherent ability to surprise?

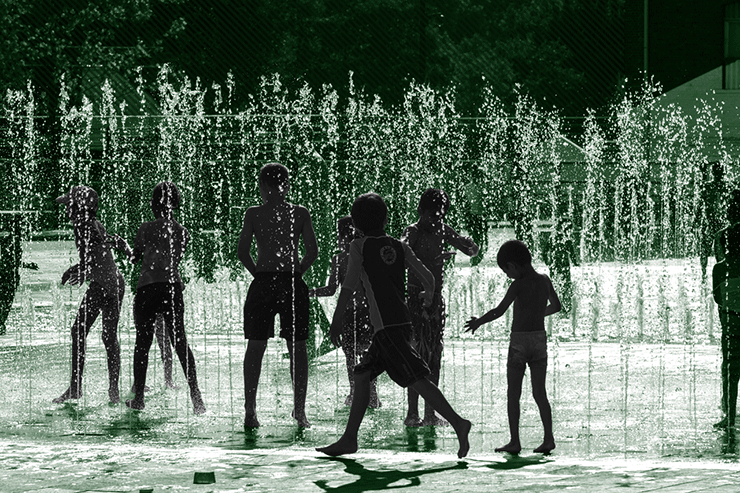

The rationale of the smart as a means for improving, designing, and building our cities has reached a tipping point of acceptability. [Image above: Robert Stainforth / Alamy Stock Photo]

Indeed, such is the take-up rate among urban planners that we are today returned to the age of the emperors—one in which it is possible and considered by some desirable to design, make, and populate a city from scratch—the most obvious example being South Korea’s Songdo, the world’s so-called smartest city.

Unfortunately, as enamoured as we are by our technological prowess, we are in danger of losing sight of what cities are all about: the experiences of people being people.

IT’S SO CLEAN, SAFE, AND PREDICTABLE AS TO BE

HYPER-HYGIENICALLY UNNATURAL. IT’S NOT HOME.

A dystopia

From the perspective of the urban planner's spreadsheet, it’s easy to see why somewhere like Songdo in South Korea might appeal.

Without history, built on reclaimed land outside of Seoul, it is a year zero purpose-built city; a clean, super-connected mega-sized business district; one that has borrowed, says its planners, from the best of the world’s greatest cities.

It has its own Venetian canal system. It has a central park. It’s underpinned by a package of "smart services," managing everything from the home, to traffic, to health. It’s made for an environmentally sustainable community. It offers, in the words of one of its key IT providers, "the ultimate lifestyle and work experience."

However, like the branded cities of old, built by kings as singular testaments to their omniscient powers, Songdo is also the result of a fundamental misunderstanding of what it takes for a city to be a city.

A joint venture between American developers, South Korean constructors, and local government, it mistakes people for categories of user, re-imagining the experiences of those categories—financiers, technologists, bio-pharmacists, commuters, residents, patients, relaxers—as part of a vast and predetermined system of input-output solutions, one so technologically advanced as to have done away with the need for "3-D" or "dirty," "dangerous," or "difficult" industries.

Largely bereft, therefore, of the messiness of manufacturing and municipal service industries, of crowds, of dirt, and of the organic and often anarchic growth of the street, it is an invention dedicated to an "international community" of "forward-thinking individuals and companies." It’s so clean—safe and predictable—as to be hyper-hygienically unnatural. It’s not home. It’s a technocrat’s wet dream, had in the 1950s.

Insert human

Much like technologists who tend to champion the democracy of the internet, so advocates of the smart city speak of the equality of access and opportunity, strategically prioritising technical platforms, infrastructure, project development, and information systems in the name of the tens of thousands of projected users.

Going even further, Songdo IBD (the city’s local authority) speaks of creating "an unparalleled quality of life as technology, resources, and innovation come together to create a world-class international community."

Leaving aside the moral implications of its somewhat rarefied class of desirable citizens, Songdo’s philosophy for city building begins with the absence of that which makes a city a city: the human.

WE ARE IN DANGER OF LOSING SIGHT OF WHAT CITIES ARE ALL ABOUT:

THE EXPERIENCES OF PEOPLE BEING PEOPLE.

Cities do not "create" communities. People form communities and cities—as Argent St George, the lead developer of King's Cross Central, stated in Principles for a Human City (2001)—are where people do life.

And by people, it means everyone who has any interest—past, present, or future—in the city. Which is why before deciding on any strategy, before making any plans, and before laying a single brick for what would become a fiendishly complex project, Argent’s chief executive Roger Madelin would meet 7500 people at 353 different meetings, to which he travelled on his bicycle.

It’s worth pausing for a moment on this, the image of the head of one of the world’s leading developers cycling about a rundown piece of London to listen to the experiences, views, and ideas of thousands of its people.

Compare this to the relatively people-less, top-of-the-value stack that serves as the smart strategy for the development of the likes of Songdo.

Indeed, compare it with the consultation process that goes into any large-sized urban development. In a recent piece of research envisioning the themes for the strategic framework for the development of an urban waterfront, the difference between what we imagined people wanted and what we discovered by getting out from behind our desks and asking was startling: while we came up with set of well-meaning, positive, and worthy themes, the people who live, work, and regularly visit the waterfront precinct were all for something much more subversive, underground, and risky.

Roger Madelin’s 353 meetings served as the evidence base for the document that sets out the philosophy of principles that sees King's Cross Central having become—17 years later—exactly what it set out to be: "a public piece of London," a mixed-use quarter, home to two primary schools, a university, a cookery school, a mobile urban garden, 2000 new homes (of which a staggering 50 percent are affordable housing), and 24 acres of open space.

This from a man on a bicycle whose vision was informed by having spent time listening to the very people his work would directly affect, perhaps for the rest of their lives. Cities, lest we forget, begin with people.

Plan for people

The King's Cross Central development is not a utopia. The key to its achievement is not to be found in its architectural prowess—which has its critics, most notably the late Zaha Hadid. It has very little to do with its adoption of smart technologies—which, though integrated, hardly compare with those that form the vast digital infrastructures of Songdo.

Rather, its success is the result of getting the first element of its strategy very right: a focus on people, and on people from all walks of life—people with an almost incomprehensibly large range of interests, needs, and dreams. It has been designed for the experience of being in the city, a design that factors in the unpredictable and choreographs the unexpected.

This capacity for designing for surprise goes beyond the logic of the machine. It goes beyond the expectations of form and function. It questions the cult of efficiency. It repurposes the physical stuff of a city as—to paraphrase the American architect Jon Jerde—the backdrop to the event that is always taking place in the space that the stuff helps create.

Thinking back on the much more radical views of those consulted over the proposed development of the waterfront, it allows for the dangerous, for the shock of the outsider, and for the experimental, while at the same time paying due homage to history, the idiosyncrasies of the local, and to the architectural heritage of the site.

DESIGNING FOR SURPRISE GOES BEYOND THE LOGIC

OF THE MACHINE (AND) THE EXPECTATIONS OF FORM AND FUNCTION.

IT QUESTIONS THE CULT OF EFFICIENCY.

In this respect, Argent’s championing of the experiences of real people over the data-truths of the spreadsheet flips the smart city value stack on its head. It’s light years away from Songdo’s rigid archaic delineation between work, rest, and play. It’s nothing like the control that smart city advocates dream of exercising over how we use the spaces in-between these delineations.

Rather than interface with a suite of smart services from the comfort of one’s technologically integrated home, it’s a design that invites those who live, work or "be" in King's Cross to use its public spaces, work places, and housing to constantly create their own city.

King's Cross Central is a vast, historically relevant urban stage, one set for scenes with narratives that play out in real time, and where the spectator—such is the importance placed on the energy of the individual, the group, and the crowd—is also the spectacle.

Full to the brim with the messiness of "the live," it shows the life of a locally informed, living community. It’s different. It’s seductive. It’s jam-packed with personality. It’s a real place.

Towards a new software

The difference between Songdo and King's Cross Central is simple. A smart city like Songdo consists of set of codes for a template for a hardwired entity that could just as well exist anywhere; its desired community defined not by the time-formed personality of a people breathing life into space through its many and multifaceted doings but rather by the curriculum vitae of a specific type of skill set.

King's Cross Central, on the other hand, could only ever be at King's Cross Central, its buildings and streets activated by the energy of the people who gave it life in the first place.

To appropriate smart-city speak, this activation is the software end of the design for any development, be that something as apparently insignificant as the coffee shop at the end of the street or something as vast and experimental as Songdo.

Rather than begin, therefore, with master planning for the hardware of a city, the infrastructure, the smart systems begin instead with its software; begin with a strategy for finding out what people want; begin with a master plan for experience.

Imagine the story of the development as the experience of the human. Design with that story in mind: employ the right people; pile resources into on-the-ground research; introduce, test, and refine the findings. From this, create a "bible" for all stakeholders, one that acts as meaning gel for all that will come.

Roger Madelin and his bike is an undoubtedly romantic explanation for the success of King's Cross Central. No doubt, he was assisted in the activation of his musings by a large and able experience design team. Even so, whatever the truth, the bible for the subsequent development was the slim, relentlessly people-focused Principles for a Human City (2001).

From it sprung a new-old "piece of London," an exemplar for what it takes to birth, manage, and complete a highly complex piece of urban planning.

Any doubts as to the proof of its ongoing success—and by extension any experience design—ought to be allayed by the following: one, Google is set to move in, drawn not by King's Cross’s smart city credentials, but rather by the fact of the area’s vibrancy, the university, the vast potential of the graduates; and two, it's where somebody called Yewon Shim, a 24-year-old graduate from Seoul, has chosen to pursue her dreams.

The first of these, Songdo would kill for. The second, it has failed—and precisely for all the reasons why King's Cross has not.

This piece was initially published in Conscious Cities: An Anthology No 2. © 2017 Conscious Cities, The Centric Lab. It is reprinted in its entirety from www.hassellstudio.com. Read the article as it appeared in the HASSELL website here.